This documentation corresponds to an older version of the product, is no longer updated, and may contain outdated information.

Please access the latest versions from https://cisco-tailf.gitbook.io/nso-docs and update your bookmarks. OK

Typical NSO services perform the necessary configuration by using

the create() callback, within a transaction tracking

the changes. This approach greatly simplifies service implementation,

but it also introduces some limitations.

For example, all provisioning is done at once, which may not be possible

or desired in all cases. In particular, network functions implemented

by containers or virtual machines often require provisioning in multiple

steps.

Another limitation is that the service mapping code must not produce

any side effects. Side effects are not tracked by the transaction and

therefore cannot be automatically reverted.

For example, imagine that there is an API call to allocate an IP address

from an external system as part of the create()

code.

The same code runs for every service change or a service re-deploy,

even during a commit dry-run, unless you take

special precautions.

So, a new IP address would be allocated every time, resulting in a

lot of waste, or worse, provisioning failures.

Nano services help you overcome these limitations. They implement a service as several smaller (nano) steps or stages, by using a technique called reactive FASTMAP (RFM), and provide a framework to safely execute actions with side effects. Reactive FASTMAP can also be implemented directly, using the CDB subscribers, but nano services offer a more streamlined and robust approach for staged provisioning.

The chapter starts by gradually introducing the nano service concepts

on a typical use-case. To aid readers working with nano services for

the first time, some of the finer points are omitted in this part

and discussed later on, in the section called “Implementation Reference”.

The latter is designed as a reference to aid you during implementation,

so it focuses on recapitulating the workings of nano services at the

expense of examples.

The rest of the chapter covers individual features with associated

use-cases and the complete working examples, which you may find in

the examples.ncs folder.

Services ideally perform the configuration all at once, with all

the benefits of a transaction, such as automatic rollback and cleanup

on errors. For nano services, this is not possible in the general

case.

Instead, a nano service performs as much configuration as possible

at the moment and leaves the rest for later. When an event occurs

that allows more work to be done, the nano service instance restarts

provisioning, by using a re-deploy action called

reactive-re-deploy.

It allows the service to perform additional configuration that was

not possible before. The process of automatic re-deploy, called

reactive FASTMAP, is repeated until the service is fully provisioned.

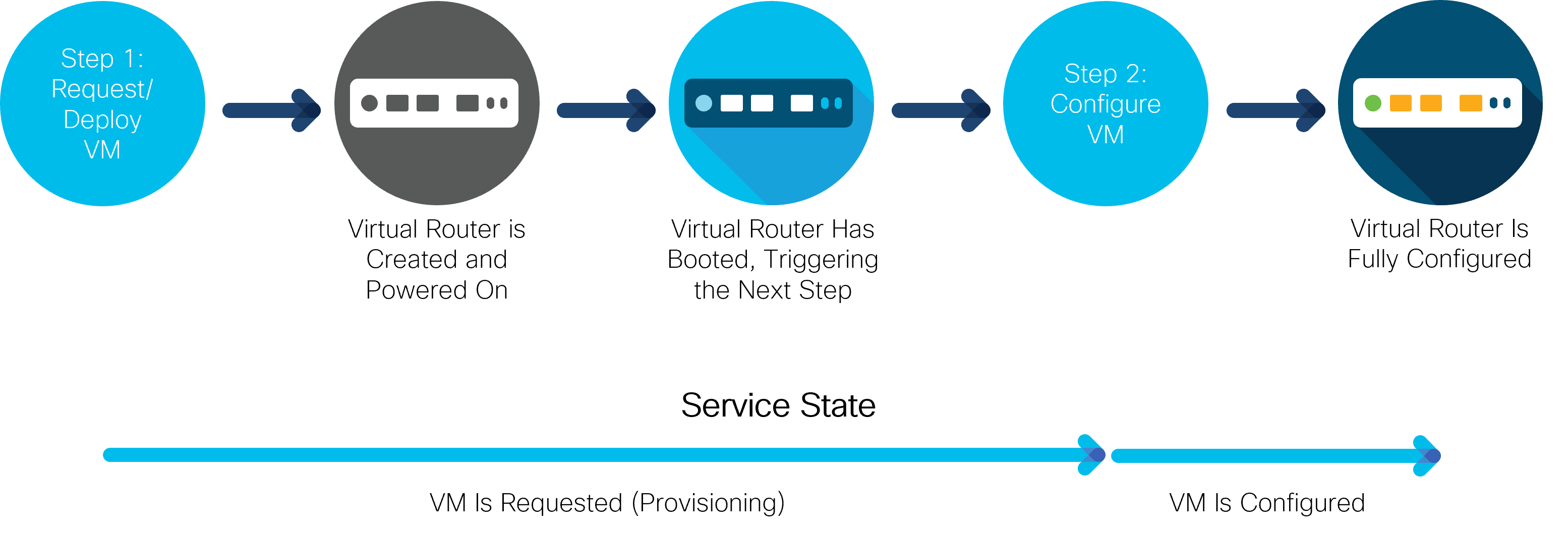

This is most evident with, for example, virtual machine (VM) provisioning, during virtual network function (VNF) orchestration. Consider a service that deploys and configures a router in a VM. When the service is first instantiated, it starts provisioning a router VM. However, it will likely take some time before the router has booted up and is ready to accept a new configuration. In turn, the service cannot configure the router just yet. The service must wait for the router to become ready. That is the event that triggers a re-deploy and the service can finish configuring the router, as the following figure illustrates:

While each step of provisioning happens inside a transaction and is still atomic, the whole service is not. Instead of a simple fully-provisioned or not-provisioned-at-all status, a nano service can be in a number of other states, depending on how far in the provisioning process it is.

The figure shows that the router VM goes through multiple states internally, however, only two states are important for the service. These two are shown as arrows, in the lower part of the figure. When a new service is configured, it requests a new VM deployment. Having completed this first step, it enters the “VM is requested but still provisioning” state. In the following step, the VM is configured and so enters the second state, where the router VM is deployed and fully configured. The states obviously follow individual provisioning steps and are used to report progress. What is more, each state tracks if an error occurred during provisioning.

For these reasons, service states are central to the design of a nano service. A list of different states, their order, and transitions between them is called a plan outline and governs the service behavior.

By default, the plan outline consists of a single

component, the self component, with

the two states init and ready. It can be used to track the progress of

the service as a whole.

You can add any number of additional components and states to form the

nano service.

The following YANG snippet, also part of the examples.ncs/development-guide/nano-services/basic-vrouter example, shows a plan outline with the two VM-provisioning states presented above:

module vrouter {

prefix vr;

identity vm-requested {

base ncs:plan-state;

}

identity vm-configured {

base ncs:plan-state;

}

identity vrouter {

base ncs:plan-component-type;

}

ncs:plan-outline vrouter-plan {

description "Plan for configuring a VM-based router";

ncs:component-type "vr:vrouter" {

ncs:state "vr:vm-requested";

ncs:state "vr:vm-configured";

}

}

}

The first part contains a definition of states as identities,

deriving from the ncs:plan-state base. These identities

are then used with the ncs:plan-outline, inside an

ncs:component-type statement. It is customary to use past

tense for state names, for example “configured-vm” or

“vm-configured” instead of “configure-vm”

and “configuring-vm.”

At present, the plan contains one component and two states but no logic. If you wish to do any provisioning for a state, the state must declare a special nano create callback, otherwise, it just acts as a checkpoint. The nano create callback is similar to an ordinary create service callback, allowing service code or templates to perform configuration. To add a callback for a state, extend the definition in the plan outline:

ncs:state "vr:vm-requested" {

ncs:create {

ncs:nano-callback;

}

}

The service automatically enters each state one by one when a new

service instance is configured. However, for the

“vm-configured” state, the service should wait until

the router VM has had the time to boot and is ready to accept

a new configuration.

An ncs:pre-condition statement in YANG provides this

functionality. Until the condition becomes fulfilled, the service

will not advance to that state.

The following YANG code instructs the nano service to check the

value of the vm-up-and-running leaf, before entering

and performing the configuration for a state.

ncs:state "vr:vm-configured" {

ncs:create {

ncs:nano-callback;

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:monitor "$SERVICE" {

ncs:trigger-expr "vm-up-and-running = 'true'";

}

}

}

}The main reason for defining multiple nano service states is to specify what part of the overall configuration belongs in each state. For the VM-router example, that entails splitting the configuration into a part for deploying a VM on a virtual infrastructure and a part for configuring it. In this case, a router VM is requested simply by adding an entry to a list of VM requests, while making the API calls is left to an external component, such as the VNF Manager.

If a state defines a nano callback, you can register a configuration

template to it. The XML template file is very similar to an ordinary

service template but requires the additional

componenttype and

state attributes in the

config-template root element.

These attributes identify which component and state in the plan

outline the template belongs to, for example:

<config-template xmlns="http://tail-f.com/ns/config/1.0" servicepoint="vrouter-servicepoint" componenttype="vr:vrouter" state="vr:vm-configured"> <devices xmlns="http://tail-f.com/ns/ncs"> <!-- ... --> </devices> </config-template>

Likewise, you can implement a callback in the service code. The registration requires you to specify the component and state, as the following Python example demonstrates:

class NanoApp(ncs.application.Application):

def setup(self):

self.register_nano_service('vrouter-servicepoint', # Service point

'vr:vrouter', # Component

'vr:vm-requested', # State

NanoServiceCallbacks)

The selected NanoServiceCallbacks class

then receives callbacks in the cb_nano_create()

function:

class NanoServiceCallbacks(ncs.application.NanoService):

@ncs.application.NanoService.create

def cb_nano_create(self, tctx, root, service, plan, component, state,

proplist, component_proplist):

...

The component and state

parameters allow the function to distinguish calls for different

callbacks when registered for more than one.

For most flexibility, each state defines a separate callback, allowing you to implement some with a template and others with code, all as part of the same service. You may even use Java instead of Python, as explained in the section called “Nano Service Callbacks”.

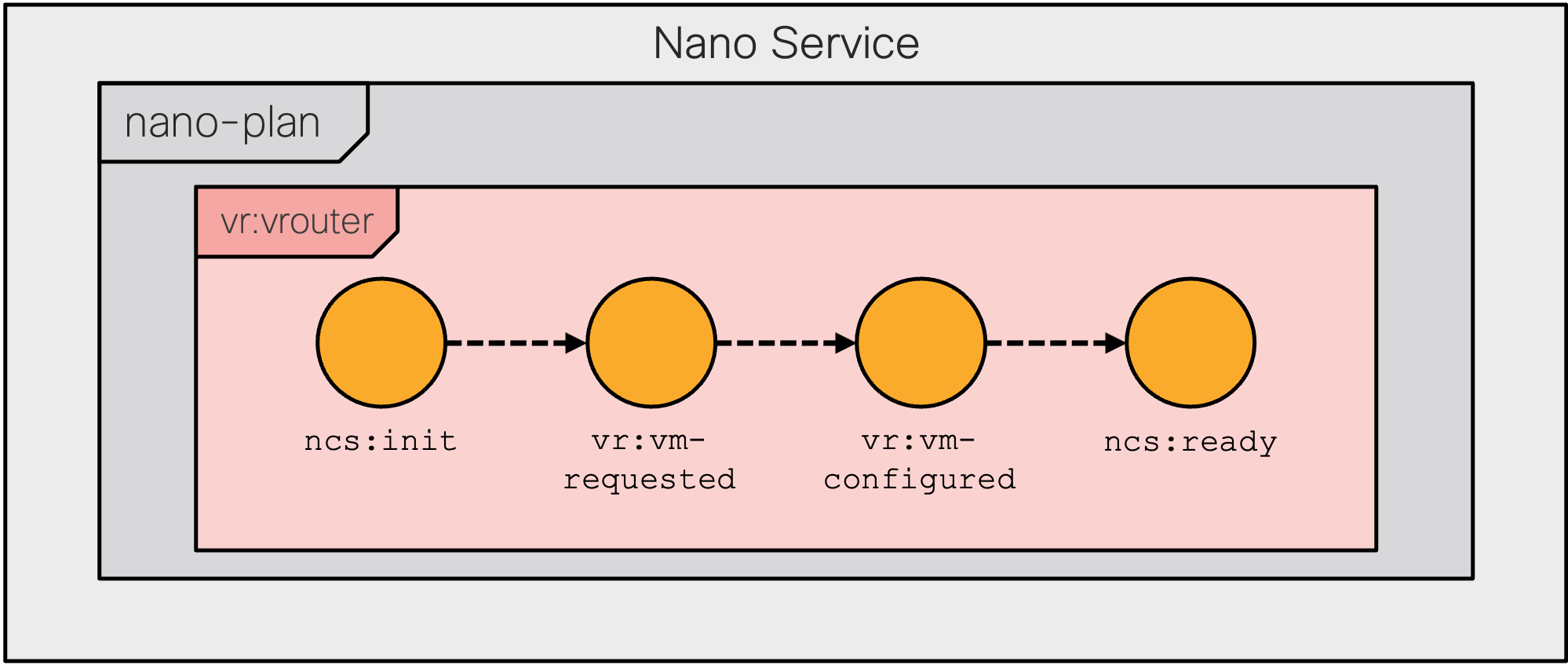

The set of states used in the plan outline describe the stages that a service instance goes through during provisioning. Naturally, these are service-specific, which presents a problem if you just want to tell whether a service instance is still provisioning or has already finished. It requires the knowledge of which state is the last, final one, making it hard to check in a generic way.

That is why each service component must have the built-in

ncs:init state as the first state and

ncs:ready as the last state.

Using the two built-in states allows for interoperability with

other services and tools. The following is a complete four-state

plan outline for the VM-based router service, with the two states

added:

ncs:plan-outline vrouter-plan {

description "Plan for configuring a VM-based router";

ncs:component-type "vr:vrouter" {

ncs:state "ncs:init";

ncs:state "vr:vm-requested" {

ncs:create {

ncs:nano-callback;

}

}

ncs:state "vr:vm-configured" {

ncs:create {

ncs:nano-callback;

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:monitor "$SERVICE" {

ncs:trigger-expr "vm-up-and-running = 'true'";

}

}

}

}

ncs:state "ncs:ready";

}

}For the service to use it, the plan outline must be linked to a service point with the help of a behavior tree. The main purpose of a behavior tree is to allow a service to dynamically instantiate components, based on service parameters. Dynamic instantiation is not always required and the behavior tree for a basic, static, single-component scenario boils down to the following:

ncs:service-behavior-tree vrouter-servicepoint {

description "A static, single component behavior tree";

ncs:plan-outline-ref "vr:vrouter-plan";

ncs:selector {

ncs:create-component "'vrouter'" {

ncs:component-type-ref "vr:vrouter";

}

}

}

This behavior tree always creates a single “vrouter”

component for the service. The service point is provided as an

argument to the ncs:service-behavior-tree statement,

while the ncs:plan-outline-ref statement provides

the name for the plan outline to use.

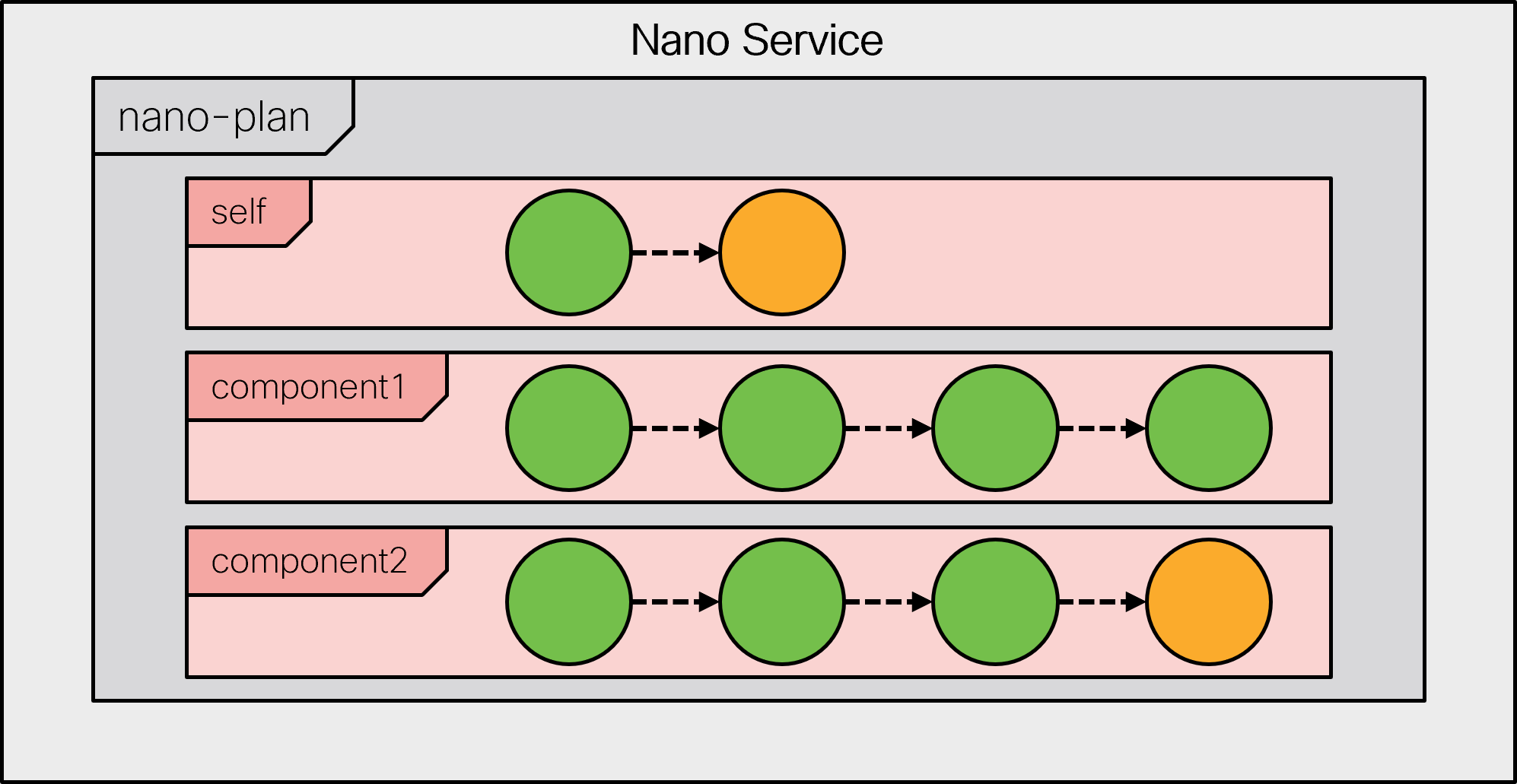

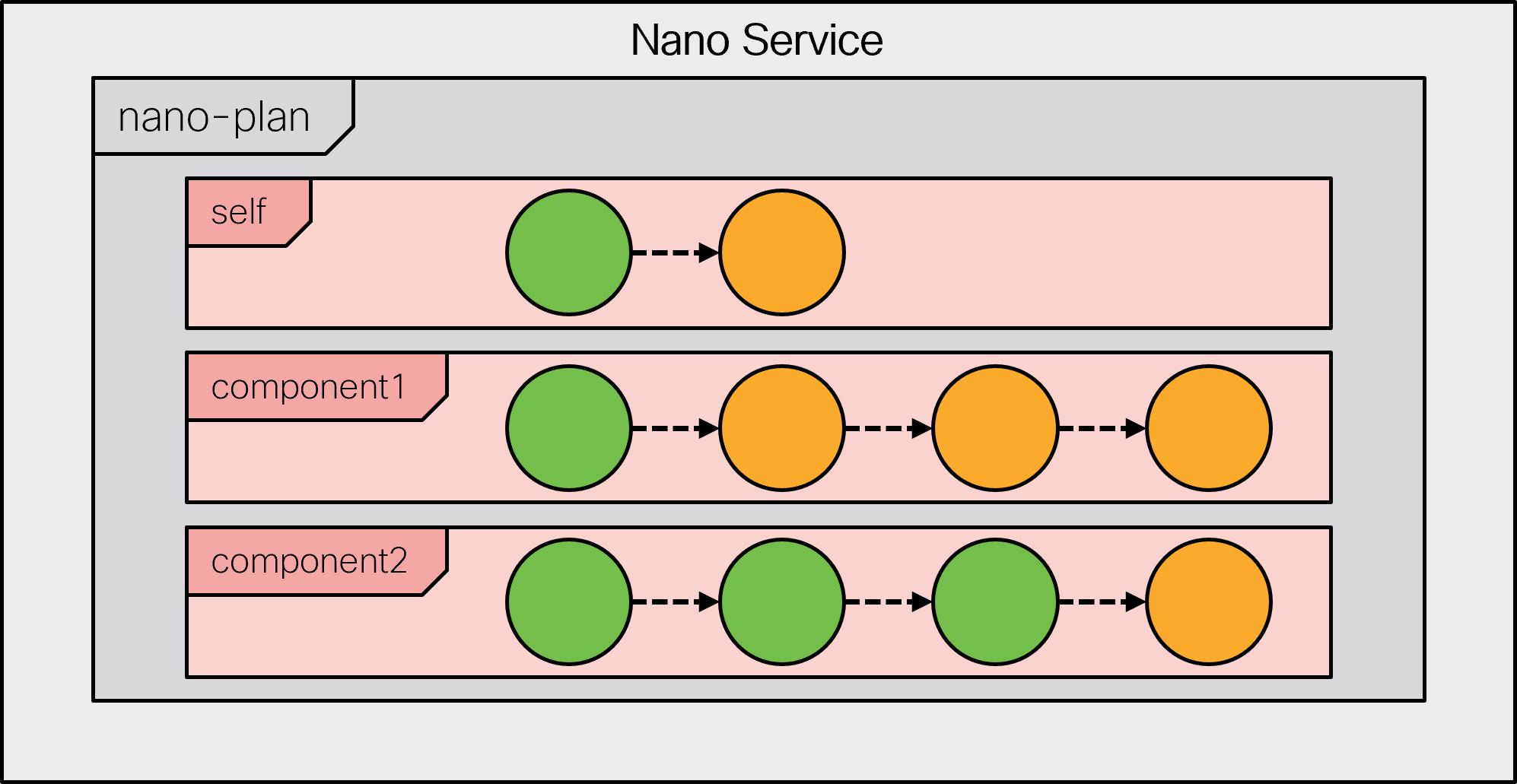

The following figure visualizes the resulting service plan and its states.

Along with the behavior tree, a nano service also relies on the

ncs:nano-plan-data grouping in its service model. It

is responsible for storing state and other provisioning details

for each service instance. Other than that, the nano service model

follows the standard YANG definition of a service:

list vrouter {

description "Trivial VM-based router nano service";

uses ncs:nano-plan-data;

uses ncs:service-data;

ncs:servicepoint vrouter-servicepoint;

key name;

leaf name {

type string;

}

leaf vm-up-and-running {

type boolean;

config false;

}

}

This model includes the operational vm-up-and-running

leaf, that the example plan outline depends on. In practice, however,

a plan outline is more likely to reference values provided by

another part of the system, such as the actual, externally provided,

state of the provisioned VM.

A nano service does not directly use its service point for configuration. Instead, the service point invokes a behavior tree to generate a plan, and the service starts executing according to this plan. As it reaches a certain state, it performs the relevant configuration for that state.

For example, when you create a new instance of the VM-router service,

the vm-up-and-running leaf is not set, so only the first

part of the service runs. Inspecting the service instance plan

reveals the following:

admin@ncs# show vrouter vr-01 plan

POST

BACK ACTION

TYPE NAME TRACK GOAL STATE STATUS WHEN ref STATUS

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

self self false - init reached 2023-08-11T07:45:20 - -

ready not-reached - - -

vrouter vrouter false - init reached 2023-08-11T07:45:20 - -

vm-requested reached 2023-08-11T07:45:20 - -

vm-configured not-reached - - -

ready not-reached - - -Since neither the “init” nor the “vm-requested” states have any pre-conditions, they are reached right away. In fact, NSO can optimize it into a single transaction (this behavior can be disabled if you use forced commits, discussed later on).

But the process has stopped at the “vm-configured”

state, denoted by the not-reached status in

the output. It is waiting for the pre-condition to become fulfilled

with the help of a kicker.

The job of the kicker is to watch the value and perform an action,

the reactive re-deploy, when the conditions are satisfied. The kickers

are managed by the nano service subsystem: when an unsatisfied

precondition is encountered, a kicker is configured, and when the

precondition becomes satisfied, the kicker is removed.

You may also verify, through the get-modifications

action, that only the first part, the creation of the VM, was

performed:

admin@ncs# vrouter vr-01 get-modifications

cli {

local-node {

data +vm-instance vr-01 {

+ type csr-small;

+}

}

}

At the same time, a kicker was installed under the kickers

container but you may need to use the unhide debug

command to inspect it. More information on kickers in general

is available in Kicker .

At a later point in time, the router VM becomes ready, and the

vm-up-and-running leaf is set to a true

value. The installed kicker notices the change and automatically

calls the reactive-re-deploy action on the service instance.

In turn, the service gets fully deployed.

admin@ncs# show vrouter vr-01 plan

POST

BACK ACTION

TYPE NAME TRACK GOAL STATE STATUS WHEN ref STATUS

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

self self false - init reached 2023-08-11T07:45:20 - -

ready reached 2023-08-11T07:47:36 - -

vrouter vrouter false - init reached 2023-08-11T07:45:20 - -

vm-requested reached 2023-08-11T07:45:20 - -

vm-configured reached 2023-08-11T07:47:36 - -

ready reached 2023-08-11T07:47:36 - -The get-modifications output confirms this fact. It contains the additional IP address configuration, performed as part of the “vm-configured” step:

admin@ncs# vrouter vr-01 get-modifications

cli {

local-node {

data +vm-instance vr-01 {

+ type csr-small;

+ address 198.51.100.1;

+}

}

}The “ready” state has no additional pre-conditions, allowing NSO to reach it along with the “vm-configured” state. This effectively breaks the provisioning process into two steps. To break it down further, simply add more states with corresponding pre-conditions and create logic.

Other than staged provisioning, nano services act the same as other services, allowing you to use the service check-sync and similar actions, for example. But please note the un-deploy and re-deploy actions may behave differently than expected, as they deal with provisioning. Chiefly, a re-deploy reevaluates the pre-conditions, possibly generating a different configuration if a pre-condition depends on operational values that have changed. The un-deploy action, on the other hand, removes all of the recorded modifications, along with the generated plan.

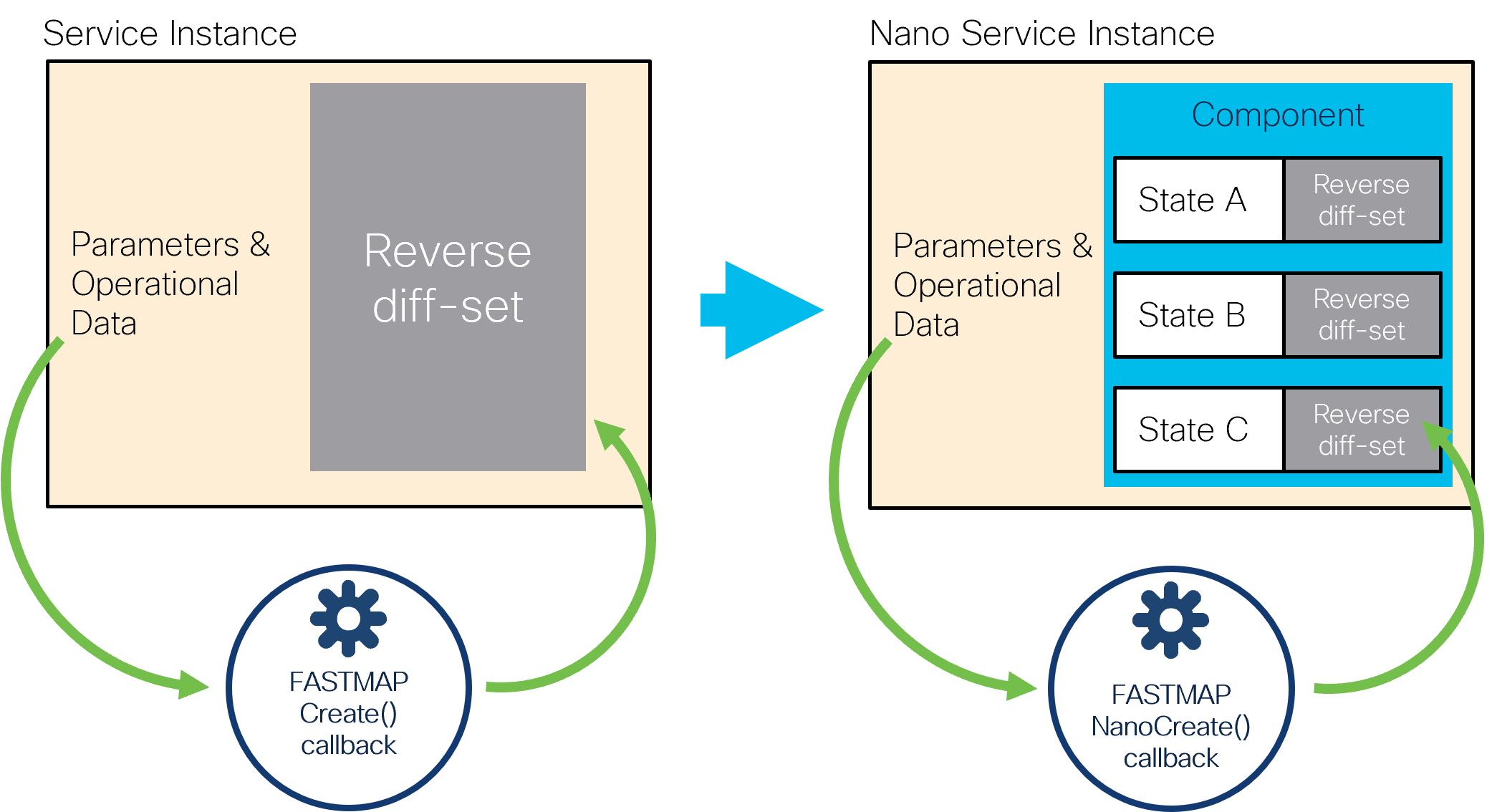

Every service in NSO has a YANG definition of the service

parameters, a service point name, and an implementation of the

service point create() callback.

Normally, when a service is committed, the FASTMAP algorithm removes

all previous data changes internally, and presents the service

data to the create() callback as if this was the

initial create.

When the create() callback returns, the FASTMAP algorithm

compares the result and calculates a reverse diff-set from the

data changes. This reverse diff-set contains the operations that

are needed to restore the configuration data to the state as it

was before the service was created. The reverse diff-set is required,

for instance, if the service is deleted or modified.

This fundamental principle is what makes the implementation of

services and the create() callback simple. In turn,

a lot of the NSO functionality relies on this mechanism.

However, in the reactive FASTMAP pattern the create()

callback is re-entered several times by using the subsequent

reactive-re-deploy calls. Storing all changes in a

single reverse diff-set then becomes an impediment. For instance,

if a staged delete is necessary, there is no way to single out

which changes has each RFM step performed.

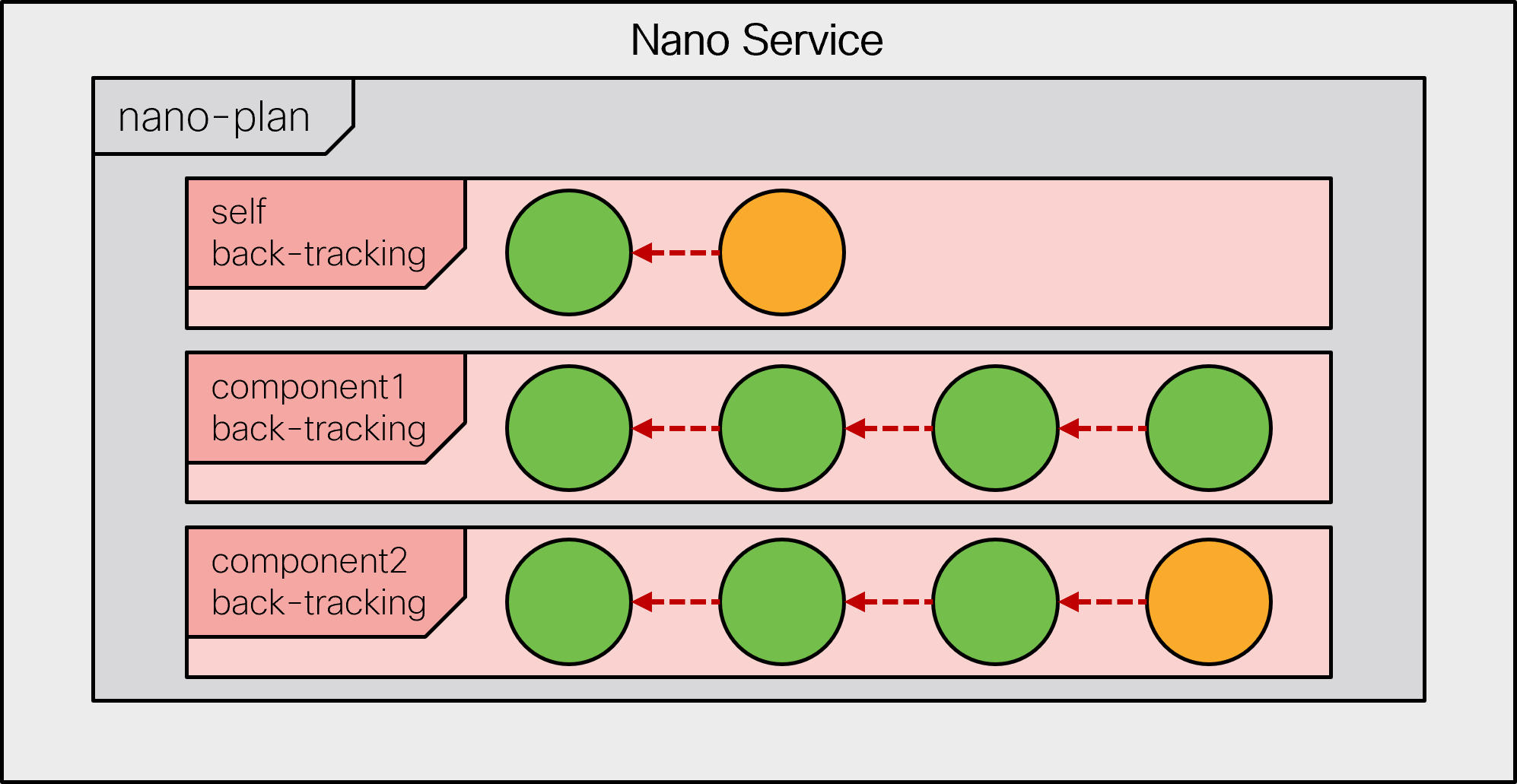

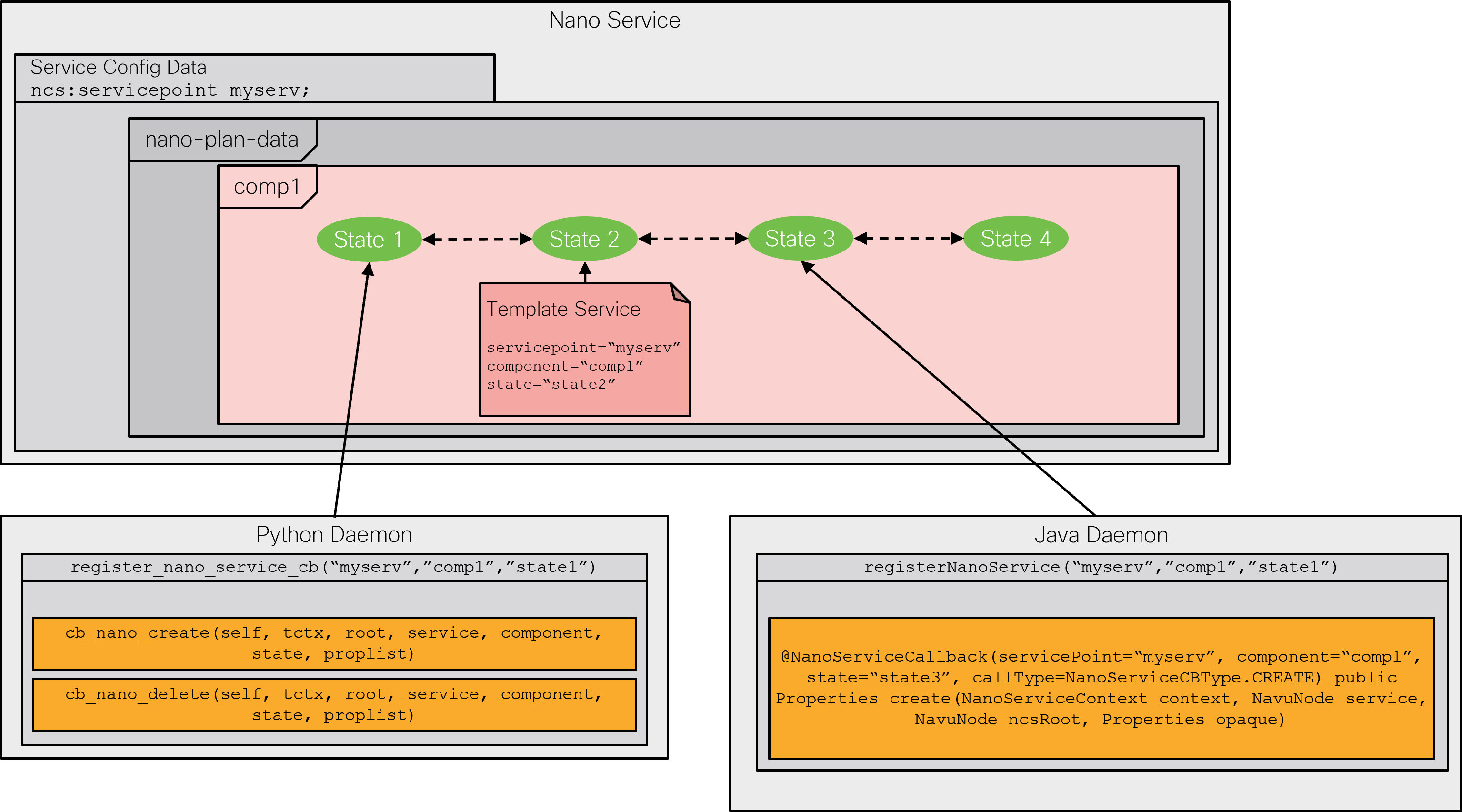

A nano service abandons the single reverse diff-set by introducing

nano-plan-data and a new NanoCreate()

callback.

The nano-plan-data YANG grouping represents an executable

plan that the system can follow to provision the service.

It has additional storage for reverse diff-set and pre-conditions

per state, for each component of the plan.

This is illustrated in the following figure:

You can still use the service get-modifications action

to visualize all data changes performed by the service as an

aggregate.

In addition, each state also has its own get-modifications

action that visualizes the data-changes for that particular state.

It allows you to more easily identify the state and, by extension,

the code that produced those changes.

Before nano services became available, RFM services could only be

implemented by creating a CDB subscriber. With the subscriber approach,

the service can still leverage the plan-data

grouping, which nano-plan-data is based on,

to report the progress of the service under the resulting

plan container.

But the create() callback becomes responsible for creating

the plan components, their states, and setting the status of the

individual states as the service creation progresses.

Moreover, implementing a staged delete with a subscriber often requires

keeping the configuration data outside of the service. The code

is then distributed between the service create() callback

and the correlated CDB subscriber.

This all results in several sources which potentially contain errors

that are complicated to track down. Nano services, on the other hand,

do not require any use of CDB subscribers or other mechanisms outside

of the service code itself to support the full service life cycle.

Resource deprovisioning is an important part of the service life cycle. The FASTMAP algorithm ensures that no longer needed configuration changes in NSO are removed automatically but that may be insufficient by itself. For example, consider the case of a VM-based router, such as the one described earlier. Perhaps provisioning of the router also involves assigning a license from a central system to the VM and that license must be returned when the VM is decommissioned. If releasing the license must be done by the VM itself, simply destroying it will not work.

Another example is management of a web server VM for a web application. Here, each VM is part of a larger pool of servers behind a load balancer that routes client requests to these servers. During deprovisioning, simply stopping the VM interrupts the currently processing requests and results in client timeouts. This can be avoided with a graceful shutdown, which stops the load balancer from sending new connections to the server and waits for the current ones to finish, before removing the VM.

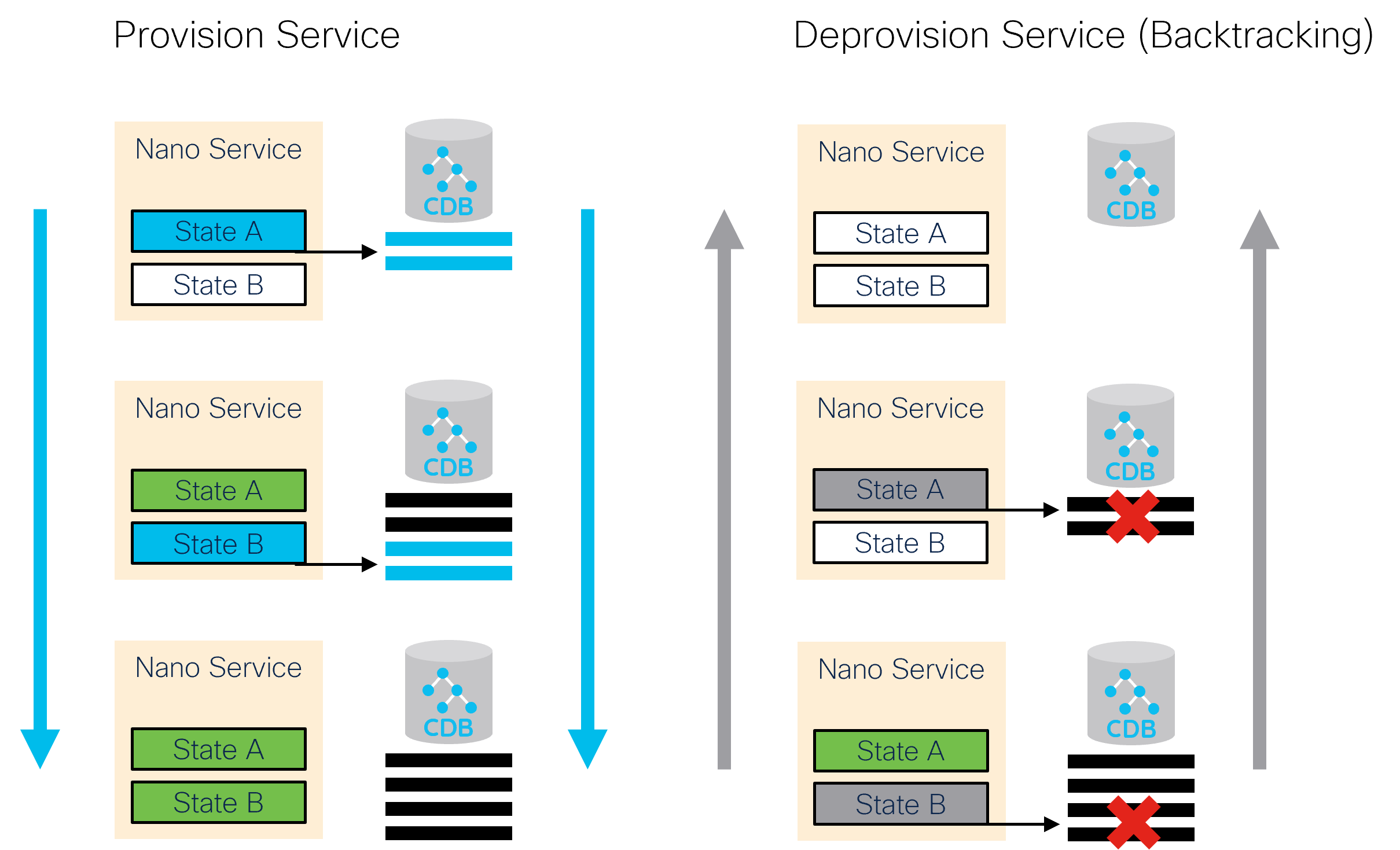

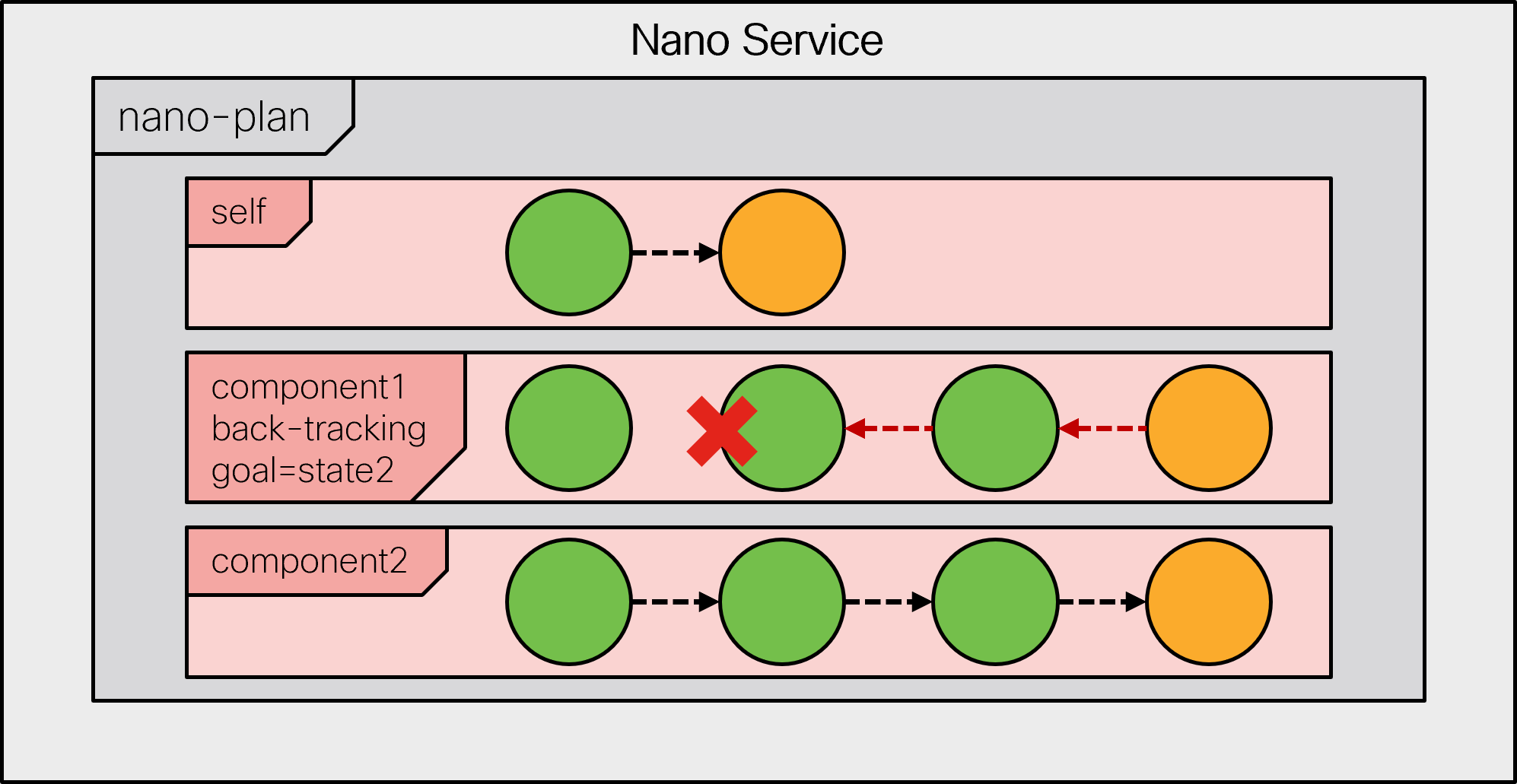

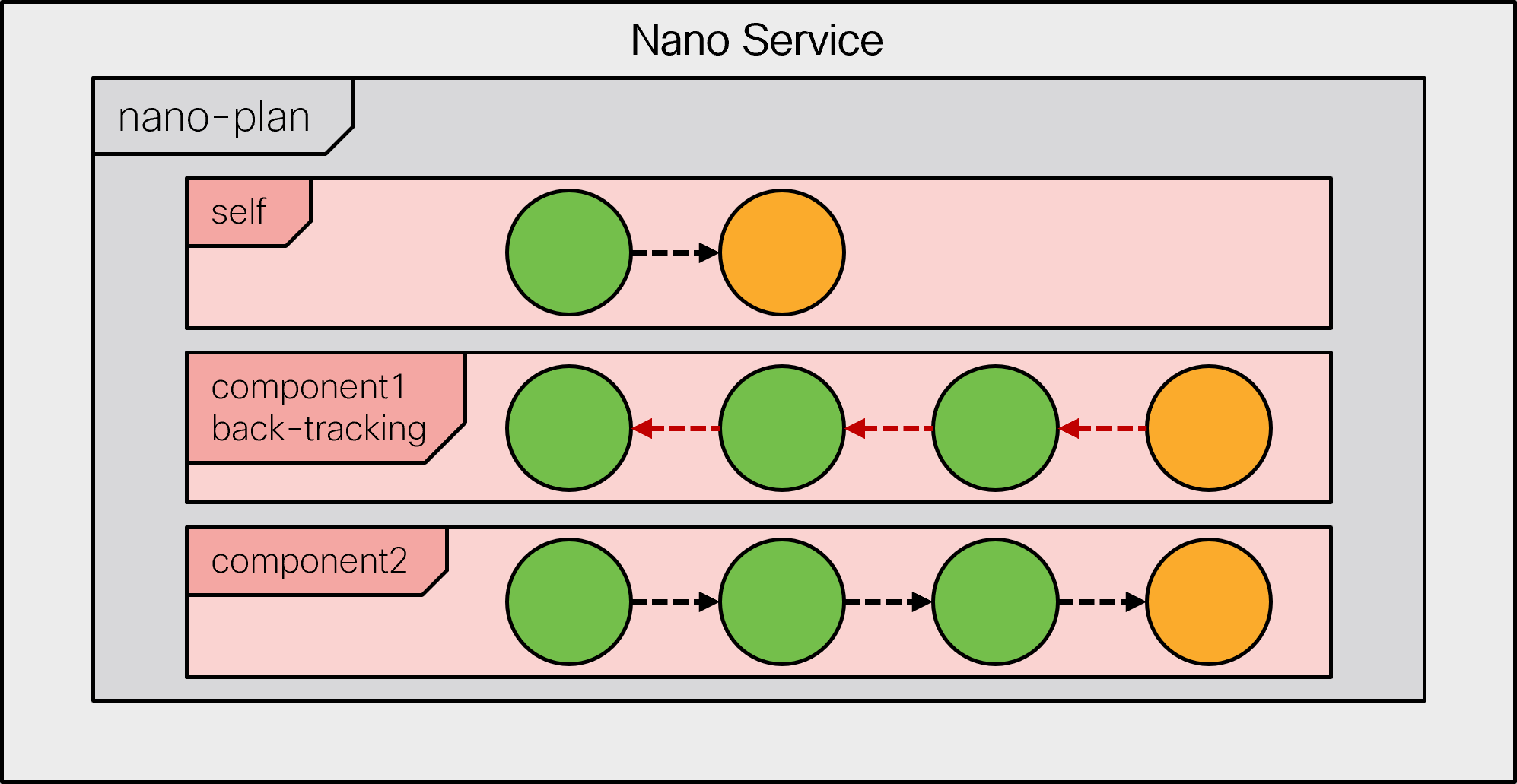

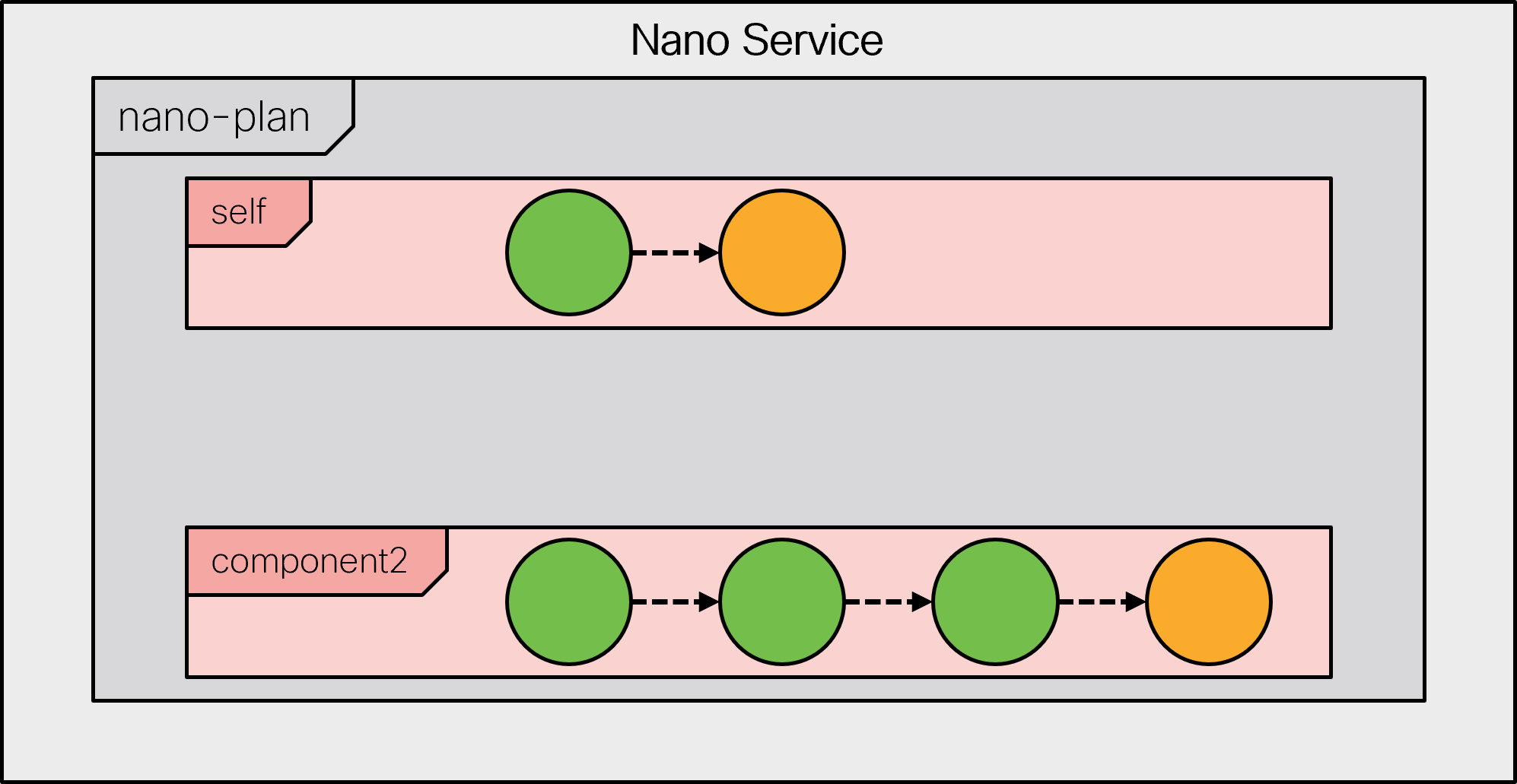

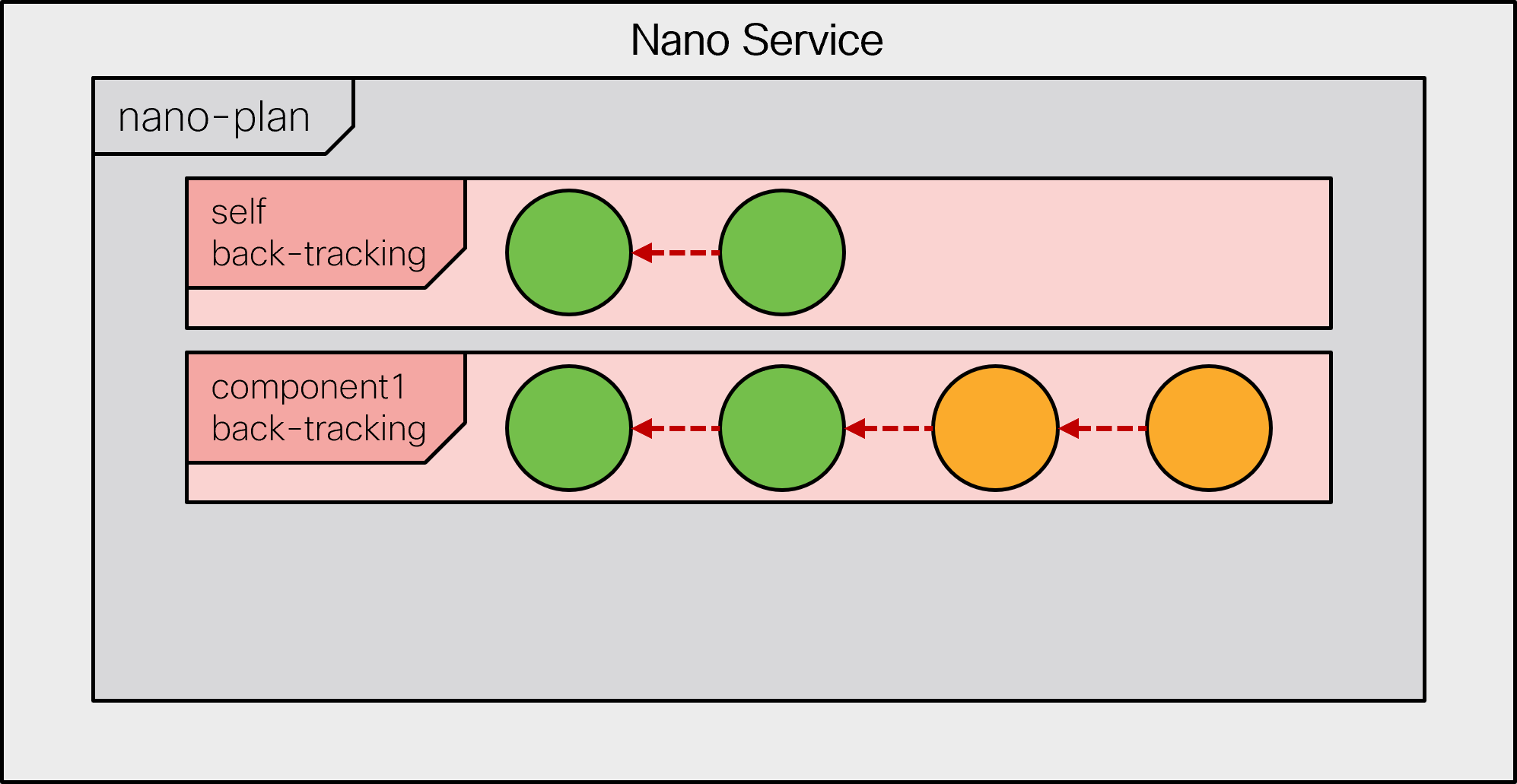

Both examples require two distinct steps for deprovisioning. Can nano services be of help in this case? Certainly. In addition to the state-by-state provisioning of the defined components, the nano service system in NSO is responsible for back-tracking during their removal. This process traverses all reached states in the reverse order, removing the changes previously done for each state one by one.

In doing so, the back-tracking process checks for a delete pre-condition of a state. A delete pre-condition is similar to the create pre-condition, but only relevant when back-tracking. If the condition is not fulfilled, the back-tracking process stops and waits until it becomes satisfied. Behind the scenes, a kicker is configured to restart the process when that happens.

If the state's delete pre-condition is fulfilled, back-tracking

first removes the state's create changes recorded by FASTMAP and

then invokes the nano delete() callback, if defined.

The main use of the callback is to override or veto the default

status calculation for a back-tracking state. That is why you can't

implement the delete() callback with a template, for

example.

Very importantly, delete() changes are not kept in

a service's reverse diff-set and may stay even after the service

is completely removed. In general, you are advised to avoid writing

any configuration data because this callback is called under a removal

phase of a plan component where new configuration is seldom expected.

Since the “create” configuration is automatically removed,

without the need for a separate delete() callback,

these callbacks are used only in specific cases and are not very

common. Regardless, the delete() callback may run as

part of the commit dry-run command, so it must

not invoke further actions or cause side effects.

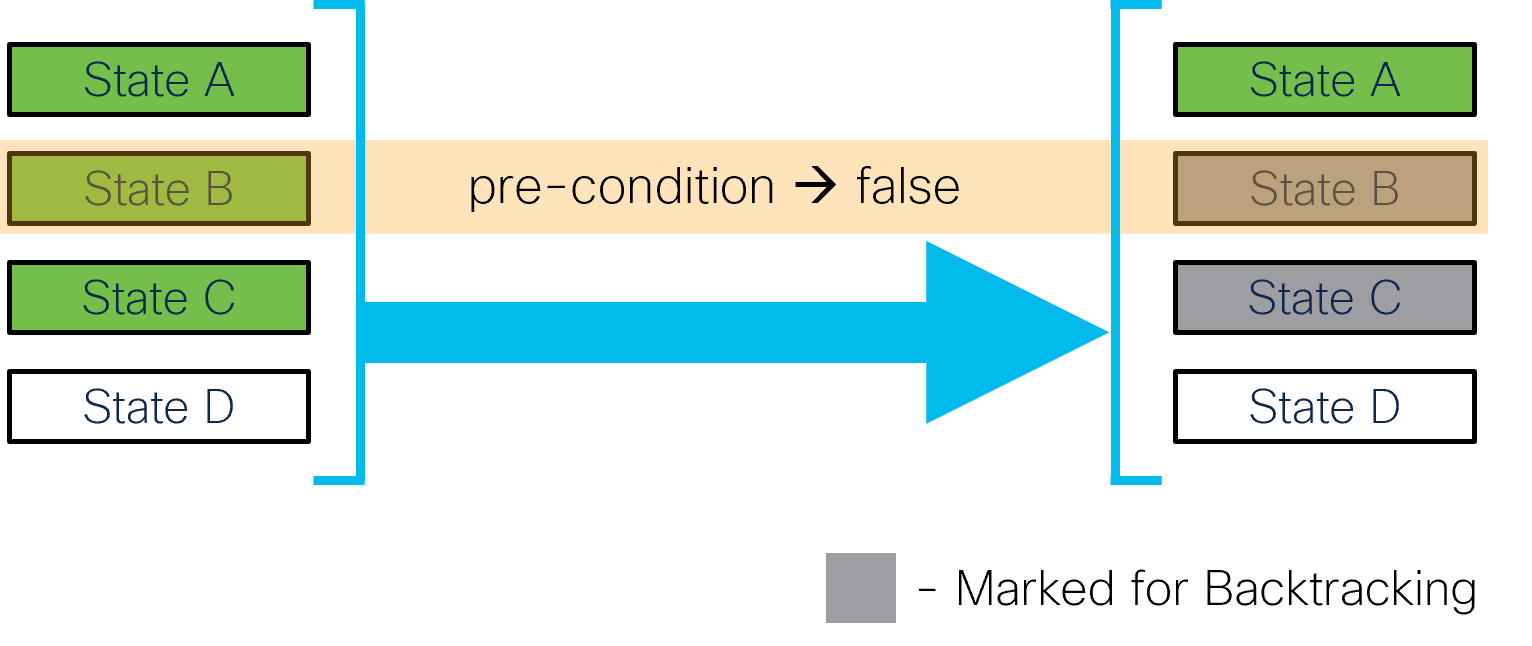

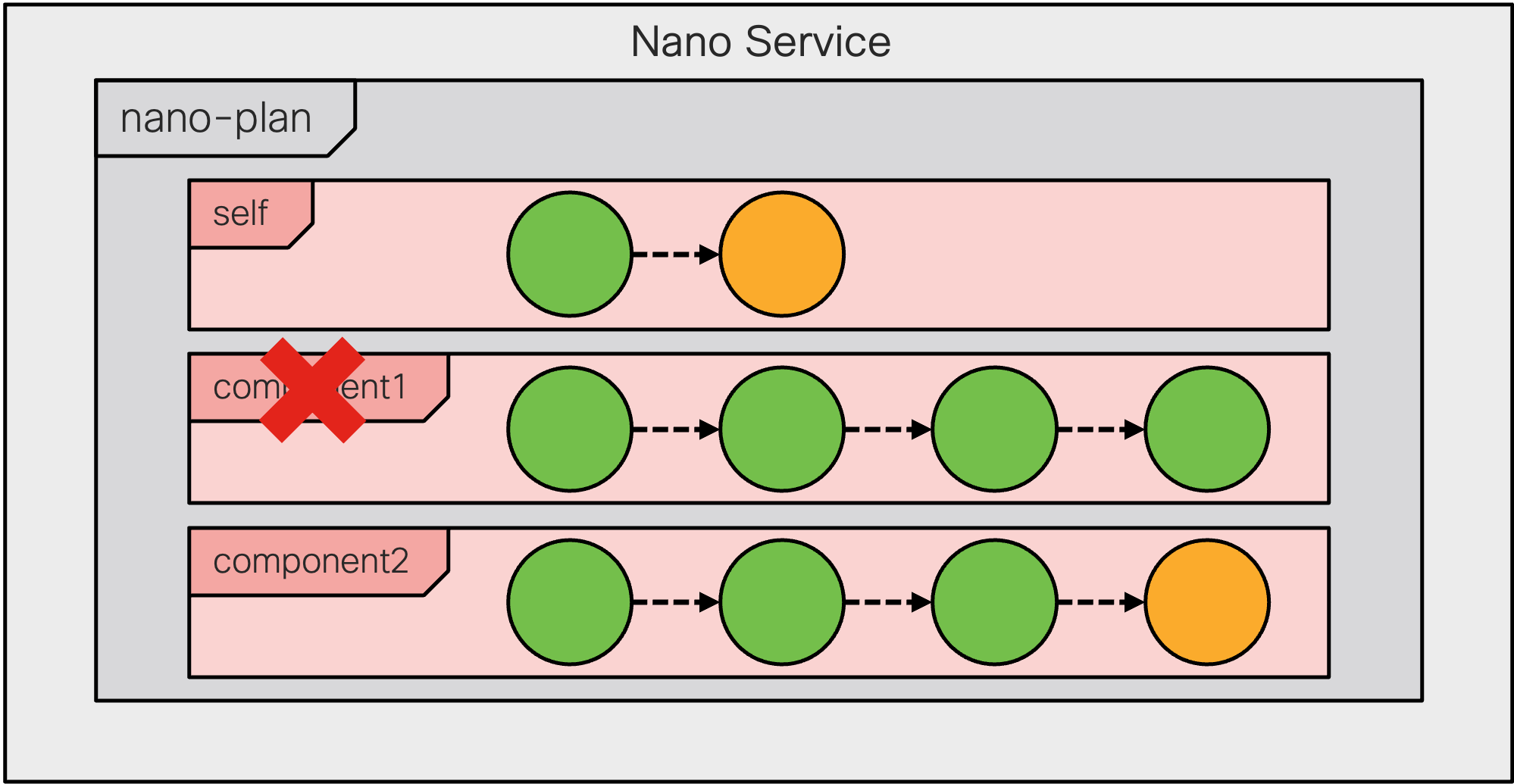

Backtracking is invoked when a component of a nano service is removed, such as when deleting a service. It is also invoked when evaluating a plan and a reached state's create pre-condition is no longer satisfied. In this case, the affected component is temporarily set to back-tracking mode for as long as it contains such nonconforming states. It allows the service to recover and return to a well-defined state.

To implement the delete pre-condition or the delete()

callback, you must add the ncs:delete statement to

the relevant state in the plan outline. Applying it to the web server

example above, you might have:

ncs:state "vr:vm-requested" {

ncs:create { ... }

ncs:delete {

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:monitor "$SERVICE" {

ncs:trigger-expr "requests-in-processing = '0'";

}

}

}

}

ncs:state "vr:vm-configured" {

ncs:create { ... }

ncs:delete {

ncs:nano-callback;

}

}

While, in general, the delete() callback should not

produce any configuration, the graceful shutdown scenario is one

of the few exceptional cases where this may be required.

Here, the delete() callback allows you to re-configure

the load balancer to remove the server from actively accepting new

connections, such as marking it “under maintenance.”

The delete pre-condition allows you to further delay the VM removal

until the ongoing requests are completed.

Similar to the create() callback, the

ncs:nano-callback statement instructs NSO to

also process a delete() callback. A Python class that

you have registered for the nano service must then implement the

following method:

@NanoService.delete

def cb_nano_delete(self, tctx, root, service, plan, component, state,

proplist, component_proplist):

...

As explained, there are some uncommon cases where additional

configuration with the delete() callback is required.

However, a more frequent use of the ncs:delete statement

is in combination with side-effect actions.

In some scenarios, side effects are an integral part of the provisioning

process and cannot be avoided. The aforementioned example on license

management may require calling a specific device action. Even so,

the create() or delete() callbacks, nano

service or otherwise, are a bad fit for such work.

Since these callbacks are invoked during the transaction commit,

no RPCs or other access outside of the NSO datastore are allowed.

If allowed, they would break the core NSO functionality, such

as a dry-run, where side-effects are not expected.

A common solution is to perform these actions outside of the

configuration transaction. Nano services provide this functionality

through the post-actions mechanism, using

a post-action-node statement for a state. It is a

definition of an action that should be invoked after the state has

been reached and the commit performed. To ensure the latter, NSO

will commit the current transaction before executing the post-action

and advancing to the next state.

The service's plan state data also carries a

post-action-status leaf, which reflects whether

the action was executed and if it was successful. The leaf will

be set to not-reached, create-reached,

delete-reached, or failed, depending on

the case and result.

If the action is still executing, then the leaf will show either

a create-init or delete-init status

instead.

Moreover, post actions can be run either asynchronously (default)

or synchronously. To run them synchronously, add a sync

statement to the post-action statement. When a post action is run

asynchronously, further states will not wait for the action to finish,

unless you define an explicit post-action-status

precondition.

While for a synchronous post action, later states in the same component

will be invoked only after the post action is run successfully.

The exception to this setting is when a component switches to a backtracking mode. In that case, the system will not wait for any create post action to complete (synchronous or not) but will start executing backtracking right away. It means a delete callback or a delete post action for a state may run before its synchronous create post action has finished executing.

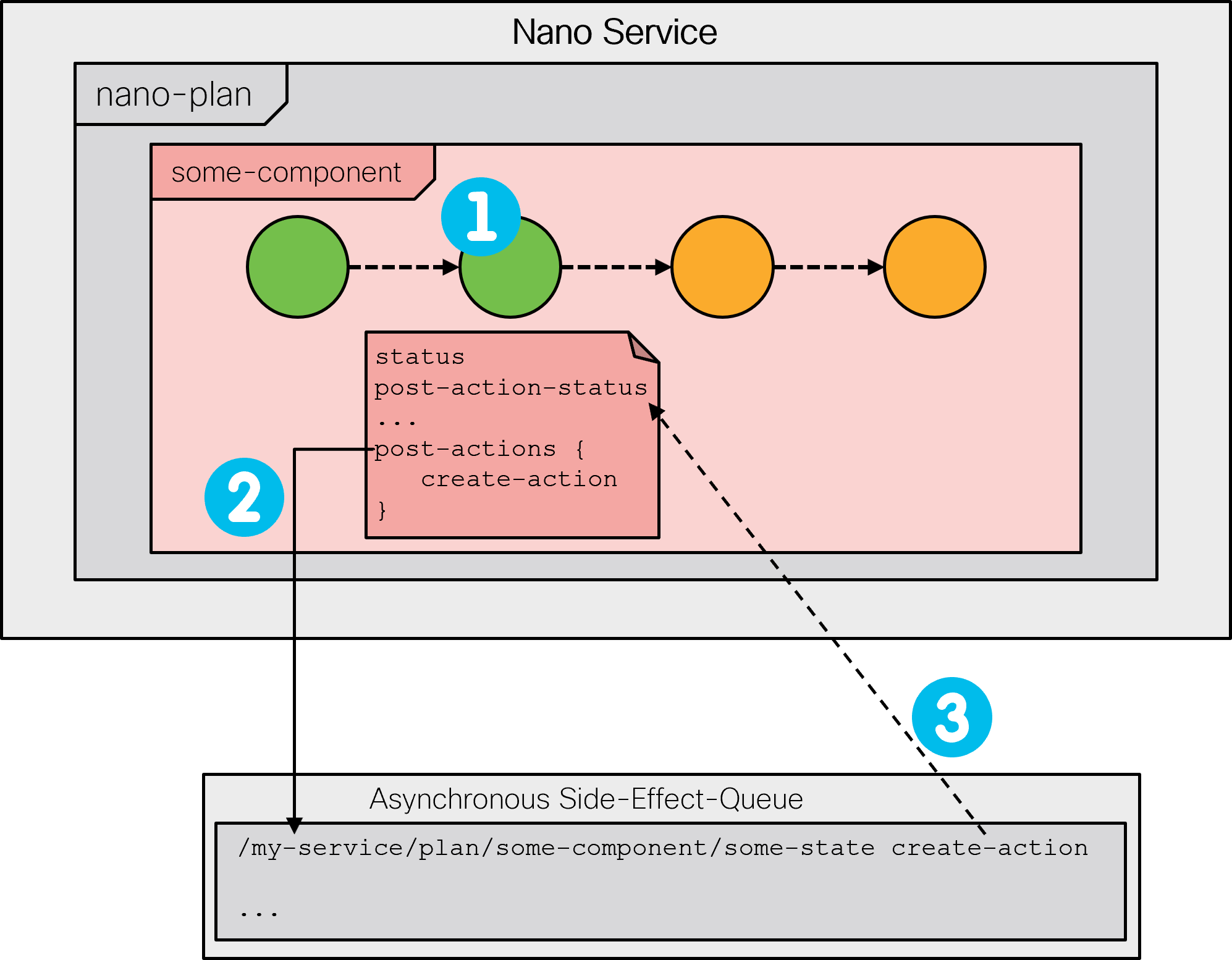

The side-effect-queue and a corresponding kicker are responsible for invoking the actions on behalf of the nano service and reporting the result in the respective state's post-action-status leaf. The following figure shows an entry is made in the side-effect-queue (2) after the state is reached (1) and its post-action-status is updated (3) once the action finishes executing.

You can use the show side-effect-queue command

to inspect the queue. The queue will run multiple actions in parallel

and keep the failed ones for you to inspect.

Please note that High Availability (HA) setups

require special consideration: the side effect queue is disabled

when High Availability is enabled and the High Availability mode is

NONE. See the section called “Mode of operation” in Administration Guide for more details.

In case of a failure, a post action sets the post-action-status

accordingly and, if the action is synchronous, the nano service

stops progressing. To retry the failed action, you can perform

the action reschedule.

$ ncs_cli -u admin admin@ncs>show side-effect-queue side-effect statusID STATUS ------------ 2 failed [ok][2023-08-15 11:01:10] admin@ncs>request side-effect-queue side-effect 2 rescheduleside-effect-id 2 [ok][2023-08-15 11:01:18]

Or execute a (reactive) re-deploy, which will also restart the nano service if it was stopped.

Using the post-action mechanism, it is possible to define side effects

for a nano service in a safe way. A post-action is only executed

one time. That is, if the post-action-status is already at the

create-reached in the create case or

delete-reached in the delete case, then new calls of

the post-actions are suppressed. In dry-run operations, post-actions

are never called.

These properties make post actions useful in a number of scenarios. A widely applicable use case is invoking a service self-test as part of initial service provisioning.

Another example, requiring the use of post-actions, is the IP address

allocation scenario from the chapter introduction. By its nature,

the allocation or assignment call produces a side effect in an external

system: it marks the assigned IP address in use. The same is true

for releasing the address.

Since NSO doesn't know how to reverse these effects on its

own, they can't be part of any create() callback. Instead,

the API calls can be implemented as post-actions.

The following snippet of a plan outline defines a create and delete post-action to handle IP management:

ncs:state "ncs:init" {

ncs:create {

ncs:post-action-node "$SERVICE" {

ncs:action-name "allocate-ip";

ncs:sync;

}

}

}

ncs:state "vr:ip-allocated" {

ncs:delete {

ncs:post-action-node "$SERVICE" {

ncs:action-name "release-ip";

}

}

}

Let's see how this plan manifests during provisioning. After the

first (init) state is reached and committed, it fires off an allocation

action on the service instance, called allocate-ip.

The job of the allocate-ip action is to communicate with

the external system, the IP Address Management (IPAM), and allocate

an address for the service instance.

This process may take a while, however it does not tie up NSO,

since it runs outside of the configuration transaction and other

configuration sessions can proceed in the meantime.

The $SERVICE XPath variable is automatically populated

by the system and allows you to easily reference the service instance.

There are other automatic variables defined. You can find the

complete list inside the tailf-ncs-plan.yang

submodule, in the $NCS_DIR/src/ncs/yang/ folder.

Due to the ncs:sync statement, service provisioning

can continue only after the allocation process (the action) completes.

Once that happens, the service resumes processing in the ip-allocated

state, with the IP value now available for configuration.

On service deprovisioning, the back-tracking mechanism works backwards

through the states. When it is the ip-allocated state's turn to

deprovision, NSO reverts any configuration done as part of

this state, and then runs the release-ip action, defined

inside the ncs:delete block.

Of course, this only happens if the state previously had a reached

status. Implemented as a post-action, release-ip can

safely use the external IPAM API to deallocate the IP address, without

impacting other sessions.

The actions, as defined in the example, do not take any parameters.

When needed, you may pass additional parameters from the service's

opaque and component_proplist object.

These parameters must be set in advance, for example in some previous

create callback. For details, please refer to the YANG definition

of post-action-input-params in the

tailf-ncs-plan.yang file.

The discussion on basic concepts briefly mentions the role of a nano behavior tree but it does not fully explore its potential. Let's now consider in which situations you may find a non-trivial behavior tree beneficial.

Suppose you are implementing a service that requires not one but two VMs. While you can always add more states to the component, these states are processed sequentially. However, you might want to provision the two VMs in parallel, since they take a comparatively long time, and it makes little sense having to wait until the first one is finished before starting with the second one. Nano services provide an elegant solution to this challenge in the form of multiple plan components: provisioning of each VM can be tracked by a separate plan component, allowing the two to advance independently, in parallel.

If the two VMs go through the same states, you can use a single component-type in the plan outline for both. It is the job of the behavior tree to create or synthesize actual components for each service instance. Therefore, you could use a behavior tree similar to the following example:

ncs:service-behavior-tree multirouter-servicepoint {

description "A 2-VM behavior tree";

ncs:plan-outline-ref "vr:multirouter-plan";

ncs:selector {

ncs:create-component "'vm1'" {

ncs:component-type-ref "vr:router-vm";

}

ncs:create-component "'vm2'" {

ncs:component-type-ref "vr:router-vm";

}

}

}

The two ncs:create-component statements instruct NSO

to create two components, named vm1 and

vm2, of the same vr:router-vm

type. Note the required use of single quotes around component names,

because the value is actually an XPath expression.

The quotes ensure the name is used verbatim when the expression

is evaluated.

With multiple components in place, the implicit self

component reflects the cumulative status of the service. The ready state

of the self component will never have its status set to reached until all

other components have the ready state status set to reached and all post

actions have been run, too. Likewise, during backtracking, the init state

will never be set to “not-reached” until all other

components have been fully backtracked and all delete post actions have

been run.

Additionally, the self ready or init state status will be set to

failed if any other state has a failed status or a failed post action,

thus signaling that something has failed while executing the service

instance.

As you can see, all the ncs:create-component statements

are placed inside an ncs:selector block. A selector

is a so-called control flow node. It selects

a group of components and allows you to decide whether they are

created or not, based on a pre-condition.

The pre-condition can reference a service parameter, which in turn

controls if the relevant components are provisioned for this service

instance. The mechanism enables you to dynamically produce just

the necessary plan components.

The pre-condition is not very useful on the top selector node, but

selectors can also be nested. For example, having a

use-virtual-devices configuration leaf in the service

YANG model, you could modify the behavior tree to the following:

ncs:service-behavior-tree multirouter-servicepoint {

description "A conditional 2-VM behavior tree";

ncs:plan-outline-ref "vr:multirouter-plan";

ncs:selector {

ncs:create-component "'router'" { ... }

ncs:selector {

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:monitor "$SERVICE" {

ncs:trigger-expr "use-virtual-devices = 'true'";

}

}

ncs:create-component "'vm1'" { ... }

ncs:create-component "'vm2'" { ... }

}

}

}

The described behavior tree always synthesizes the router component

and evaluates the child selector. However, the child selector only

synthesizes the two VM components if the service configuration requested

so by setting the use-virtual-devices to

true.

What is more, if the pre-condition value changes, the system re-evaluates the behavior tree and starts the backtracking operation for any removed components.

For even more complex cases, where a variable number of components

needs to be synthesized, the ncs:multiplier control

flow node becomes useful.

Its ncs:foreach statement selects a set of elements

and each element is processed in the following way:

-

If the optional

whenstatement is not satisfied, the element is skipped. -

All

variablestatements are evaluated as XPath expressions for this element, to produce a unique name for the component and any other element-specific values. -

All

ncs:create-componentand other control flow nodes are processed, creating the necessary components for this element.

The multiplier node is often used to create a component for each

item in a list. For example, if the service model contains a list

of VMs, with a key name, then the following code creates

a component for each of the items:

ncs:multiplier {

ncs:foreach "vms" {

ncs:variable "NAME" {

ncs:value-expr "concat('vm-', name)";

}

ncs:create-component "$NAME" { ... }

}

}

In this particular case it might be possible to avoid the variable

altogether, by using the expression for the create-component

statement directly.

However, defining a variable also makes it available to service

create() callbacks.

This is extremely useful, since you can access these values, as well as the ones from the service opaque object, directly in the nano service XML templates. The opaque, especially, allows you to separate the logic in code from applying the XML templates.

The examples.ncs/development-guide/nano-services/netsim-vrouter

folder contains a complete implementation of a service that provisions

a netsim device instance, onboards it to NSO, and pushes a sample

interface configuration to the device.

Netsim device creation is neither instantaneous nor side-effect free,

and thus requires the use of a nano service. It more closely resembles

a real-world use-case for nano services.

To see how the service is used through a prearranged scenario, execute the make demo command from the example folder. The scenario provisions and deprovisions multiple netsim devices to show different states and behaviors, characteristic of nano services.

The service, called vrouter, defines three component

types in the src/yang/vrouter.yang file:

-

vr:vrouter: A “day-0” component that creates and initializes a netsim process as a virtual router device. -

vr:vrouter-day1: A “day-1” component for configuring the created device and tracking NETCONF notifications.

As the name implies, the day-0 component must provision before the day-1 component. Since the two provision in sequence, in general, a single component would suffice. But the components are kept separate to illustrate component dependencies.

The behavior tree synthesizes each of the components for a service instance using some service-specific names. In order to do so, the example defines three variables to hold different names:

// vrouter name

ncs:variable "NAME" {

ncs:value-expr "current()/name";

}

// vrouter component name

ncs:variable "D0NAME" {

ncs:value-expr "concat(current()/name, '-day0')";

}

// vrouter day1 component name

ncs:variable "D1NAME" {

ncs:value-expr "concat(current()/name, '-day1')";

}

The vr:vrouter (day-0) component has a number

of plan states that it goes through during provisioning:

-

ncs:init

-

vr:requested

-

vr:onboarded

-

ncs:ready

The init and ready states are required as the first and last state

in all components for correct overall state tracking in

ncs:self. They have no additional logic tied

to them.

The vr:requested state represents the first step in virtual router provisioning. While it does not perform any configuration itself (no nano-callback statement), it calls a post-action that does all the work. The following is a snippet of the plan outline for this state:

ncs:state "vr:requested" {

ncs:create {

// Call a Python action to create and start a netsim vrouter

ncs:post-action-node "$SERVICE" {

ncs:action-name "create-vrouter";

ncs:result-expr "result = 'true'";

ncs:sync;

}

}

}

The create-router action calls the Python code inside

the python/vrouter/main.py file, which runs

a couple of system commands, such as the

ncs-netsim create-device and the

ncs-netsim start commands. These commands do

the same thing as you would if you performed the task manually from

the shell.

The vr:requested state also has a delete post-action, analogous to create, which stops and removes the netsim device during service deprovisioning or backtracking.

Inspecting the Python code for these post actions will reveal that a semaphore is used to control access to the common netsim resource. It is needed because multiple vrouter instances may run the create and delete action callbacks in parallel. The Python semaphore is shared between the delete and create action processes using a Python multiprocessing manager, as the example configure the NSO Python VM to start the actions in multiprocessing mode. See the section called “The application component” for details.

In vr:onboarded, the nano Python callback function from the

main.py file adds the relevant NSO device

entry for a newly-created netsim device. It also configures NSO

to receive notifications from this device through a NETCONF

subscription.

When the NSO configuration is complete, the state transitions

into the reached status, denoting the onboarding has completed

successfully.

The vr:vrouter component handles so-called

day-0 provisioning. Alongside this component, the

vr:vrouter-day1 component starts provisioning

in parallel.

During provisioning, it transitions through the following states:

-

ncs:init

-

vr:configured

-

vr:deployed

-

ncs:ready

The component reaches the init state right away. However, the vr:configured state has a precondition:

ncs:state "vr:configured" {

ncs:create {

// Wait for the onboarding to complete

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:monitor "$SERVICE/plan/component[type='vr:vrouter']" +

"[name=$D0NAME]/state[name='vr:onboarded']" {

ncs:trigger-expr "post-action-status = 'create-reached'";

}

}

// Invoke a service template to configure the vrouter

ncs:nano-callback;

}

}

Provisioning can continue only after the first component,

vr:vrouter, has executed its vr:onboarded

post-action. The precondition demonstrates how one component can

depend on another component reaching some particular state or

successfully executing a post-action.

The vr:onboarded post-action performs a sync-from

command for the new device.

After that happens, the vr:configured state can push the device

configuration according to the service parameters, by using an XML

template, templates/vrouter-configured.xml.

The service simply configures an interface with a VLAN ID and a

description.

Similarly, the vr:deployed state has its own precondition, which

makes use of the ncs:any statement. It specifies either

(any) of the two monitor statements will satisfy the precondition.

One of them checks the last received NETCONF notification contains

a link-status value of up for the

configured interface.

In other words, it will wait for the interface to become operational.

However, relying solely on notifications in the precondition can be problematic, as the received notifications list in NSO can be cleared and would result in unintentional backtracking on a service re-deploy. For this reason, there is the other monitor statement, checking the device live-status.

Once either of the conditions is satisfied, it marks the end of provisioning. Perhaps the use of notifications in this case feels a little superficial but it illustrates a possible approach to waiting for the steady state, such as routing adjacencies to form and alike.

Altogether, the example shows how to use different nano service mechanisms in a single, complex, multistage service that combines configuration and side-effects. The example also includes a Python script that uses the RESTCONF protocol to configure a service instance and monitor its provisioning status. You are encouraged to configure a service instance yourself and explore the provisioning process in detail, including service removal. Regarding removal, have you noticed how nano services can deprovision in stages, but the service instance is gone from the configuration right away?

By removing the service instance configuration from NSO, you start a service deprovisioning process. For an ordinary service, a stored reverse diff-set is applied, ensuring that all of the service-induced configuration is removed in the same transaction. For nano services, having a staged, multistep service delete operation, this is not possible. The provisioned states must be backtracked one by one, often across multiple transactions. With the service instance deleted, NSO must track the deprovisioning progress elsewhere.

For this reason, NSO mutates a nano service instance when it is removed. The instance is transformed into a zombie service, which represents the original service that still requires deprovisioning. Once the deprovisioning is complete, with all the states backtracked, the zombie is automatically removed.

Zombie service instances are stored with their service data, their

plan states, and diff-sets in a /ncs:zombies/services

list. When a service mutates to a zombie, all plan components are

set to back-tracking mode and all service pre-condition kickers

are rewritten to reference the zombie service instead.

Also, the nano service subsystem now updates the zombie plan states

as deprovisioning progresses. You can use the

show zombies service command to inspect the plan.

Under normal conditions, you should not see any zombies, except for the service instances that are actively deprovisioning. However, if an error occurs, the deprovisioning process will stop with an error status and a zombie will remain. With a zombie present, NSO will not allow creating the same service instance in the configuration tree. The zombie must be removed first.

After addressing the underlying problem, you can restart the

deprovisioning process with the re-deploy or the

reactive-re-deploy actions. The difference between

the two is which user the action uses.

The re-deploy uses the current user that initiated

the action whilst the reactive-re-deploy action keeps

using the same user that last modified the zombie service.

These zombie actions behave a bit differently than their normal service counterparts. In particular, the zombie variants perform the following steps to better serve the deprovisioning process:

-

Start a temporary transaction in which the service is reinstated (created). The service plan will have the same status as it had when it mutated.

-

Back-track plan components in a normal fashion, that is, removing device changes for states with delete pre-conditions satisfied.

-

If all components are completely back-tracked, the zombie is removed from the zombie-list. Otherwise, the service and the current plan states are stored back into the zombie-list, with new kickers waiting to activate the zombie when some delete pre-condition is satisfied.

In addition, zombie services support the resurrect action.

The action reinstates the zombie back in the configuration tree as

a real service, with the current plan status, and reverts plan

components back from back-tracking to normal mode. It is an

“undo” for a nano service delete.

In some situations, especially during nano service development,

a zombie may get stuck because of a misconfigured precondition or

similar issues. A re-deploy is unlikely to help in that case and

you may need to forcefully remove the problematic plan component.

The force-back-track action performs this job and allows

you to backtrack to a specific state, if specified. But beware that

using the action avoids calling any post-actions or delete callbacks

for the forcefully backtracked states, even though the recorded

configuration modifications are reverted.

It can and will leave your systems in an

inconsistent or broken state if you are not careful.

When a service is provisioned in stages, as nano services are, the success of the initial commit no longer indicates the service is provisioned. Provisioning may take a while and may fail later, requiring you to consult the service plan to observe the service status. This makes it harder to tell when a service finishes provisioning, for example. Fortunately, services provide a set of notifications that indicate important events in the service's life-cycle, including a successful completion. These events enable NETCONF and RESTCONF clients to subscribe to events instead of polling the plan and commit queue status.

The built-in service-state-changes NETCONF/RESTCONF stream is used

by NSO to generate northbound notifications for services,

including nano services.

The event stream is enabled by default in ncs.conf,

however, individual notification events must be explicitly configured

to be sent.

When a service's plan component changes state, the

plan-state-change notification is generated with

the new state of the plan. It includes the status, which indicates

one of not-reached, reached, or failed.

The notification is sent when the state is created,

modified, or deleted, depending on the

configuration.

For reference on the structure and all the fields present in

the notification, please see the YANG model in the

tailf-ncs-plan.yang file.

As a common use-case, an event with status

reached for the self component

ready state signifies that all nano service components

have reached their ready state and provisioning is complete.

A simple example of this scenario is included in the

examples.ncs/development-guide/nano-services/netsim-vrouter/demo.py

Python script, using RESTCONF.

To enable the plan-state-change notifications to be sent, you must enable them for a specific service in NSO. For example, can load the following configuration into the CDB as an XML initialization file:

<services xmlns="http://tail-f.com/ns/ncs"> <plan-notifications> <subscription> <name>nano1</name> <service-type>/vr:vrouter</service-type> <component-type>self</component-type> <state>ready</state> <operation>modified</operation> </subscription> <subscription> <name>nano2</name> <service-type>/vr:vrouter</service-type> <component-type>self</component-type> <state>ready</state> <operation>created</operation> </subscription> </plan-notifications> </services>

This configuration enables notifications for the self component's ready state when created or modified.

When a service is committed through the commit queue, this

notification acts as a reference regarding the state of the service.

Notifications are sent when the service commit queue item is waiting

to run, executing, waiting to be unlocked, completed, failed, or

deleted. More details on the service-commit-queue-event

notification content can be found in the YANG model inside

tailf-ncs-services.yang .

For example, the failed event can be used to detect

that a nano service instance deployment failed because a

configuration change committed through the commit queue has failed.

Measures to resolve the issue can then be taken and the nano service

instance can be re-deployed.

A simple example of this scenario is included in the

examples.ncs/development-guide/nano-services/netsim-vrouter/demo.py

Python script where the service is committed through the commit

queue, using RESTCONF. By design, the configuration commit to a

device fails, resulting in a commit-queue-notification

with the failed event status for the commit queue

item.

To enable the service-commit-queue-event notifications to be sent, you can load the following example configuration into NSO, as an XML initialization file or some other way:

<services xmlns="http://tail-f.com/ns/ncs"> <commit-queue-notifications> <subscription> <name>nano1</name> <service-type>/vr:vrouter</service-type> </subscription> </commit-queue-notifications> </services>

The following examples demonstrate the usage and sample events for the notification functionality, described in this section, using RESTCONF, NETCONF, and CLI northbound interfaces.

RESTCONF subscription request using curl:

$ curl -isu admin:admin -X GET -H "Accept: text/event-stream"

http://localhost:8080/restconf/streams/service-state-changes/json

data: {

data: "ietf-restconf:notification": {

data: "eventTime": "2021-11-16T20:36:06.324322+00:00",

data: "tailf-ncs:service-commit-queue-event": {

data: "service": "/vrouter:vrouter[name='vr7']",

data: "id": 1637135519125,

data: "status": "completed",

data: "trace-id": "vr7-1"

data: }

data: }

data: }

data: {

data: "ietf-restconf:notification": {

data: "eventTime": "2021-11-16T20:36:06.728911+00:00",

data: "tailf-ncs:plan-state-change": {

data: "service": "/vrouter:vrouter[name='vr7']",

data: "component": "self",

data: "state": "tailf-ncs:ready",

data: "operation": "modified",

data: "status": "reached",

data: "trace-id": "vr7-1"

data: }

data: }

data: }See the section called “Streams” in Northbound APIs for further reference.

NETCONF create subscription using netconf-console:

$ netconf-console create-subscription=service-state-changes

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<notification xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:notification:1.0">

<eventTime>2021-11-16T20:36:06.324322+00:00</eventTime>

<service-commit-queue-event xmlns="http://tail-f.com/ns/ncs">

<service xmlns:vr="http://com/example/vrouter">/vr:vrouter[vr:name='vr7']</service>

<id>1637135519125</id>

<status>completed</status>

<trace-id>vr7-1</trace-id>

</service-commit-queue-event>

</notification>

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<notification xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:netconf:notification:1.0">

<eventTime>2021-11-16T20:36:06.728911+00:00</eventTime>

<plan-state-change xmlns="http://tail-f.com/ns/ncs">

<service xmlns:vr="http://com/example/vrouter">/vr:vrouter[vr:name='vr7']</service>

<component>self</component>

<state>ready</state>

<operation>modified</operation>

<status>reached</status>

<trace-id>vr7-1</trace-id>

</plan-state-change>

</notification>See the section called “Notification Capability” in Northbound APIs for further reference.

CLI show received notifications using ncs_cli:

$ ncs_cli -u admin -C <<<'show notification stream service-state-changes'

notification

eventTime 2021-11-16T20:36:06.324322+00:00

service-commit-queue-event

service /vrouter[name='vr17']

id 1637135519125

status completed

trace-id vr7-1

!

!

notification

eventTime 2021-11-16T20:36:06.728911+00:00

plan-state-change

service /vrouter[name='vr7']

component self

state ready

operation modified

status reached

trace-id vr7-1

!

!

You have likely noticed the trace-id field at the end of the example

notifications above. The trace id is an optional but very useful

parameter when committing the service configuration.

It helps you trace the commit in the emitted log messages and

the service-state-changes stream notifications.

The above notifications, taken from the

examples.ncs/development-guide/nano-services/netsim-vrouter

example, are emitted after applying a RESTCONF plain patch:

$ curl -isu admin:admin -X PATCH

-H "Content-type: application/yang-data+json"

'http://localhost:8080/restconf/data?commit-queue=sync&trace-id=vr7-1'

-d '{ "vrouter:vrouter": [ { "name": "vr7" } ] }'

Note that the trace id is specified as part of the URL. If missing, NSO will generate and assign one on its own.

At times, especially when you use an iterative development approach or simply due to changing requirements, you might need to update (change) an existing nano service and its implementation. In addition to other service update best practices, such as model upgrades, you must carefully consider the nano-service-specific aspects. The following discussion mostly focuses on migrating an already provisioned service instance to a newer version; however, the same concepts also apply while you are initially developing the service.

In the simple case, updating the model of a nano service and getting the changes to show up in an already created instance is a matter of executing a normal re-deploy. This will synthesize any new components and provision them, along with the new configuration, just like you would expect from a non-nano service.

A major difference occurs if a service instance is deleted and is in a zombie state when the nano service is updated. You should be aware that no synthetization is done for that service instance. The only goal of a deleted service is to revert any changes made by the service instance. Therefore, in that case, the synthetization is not needed. It means that, if you've made changes to callbacks, post actions, or pre-conditions, those changes will not be applied to zombies of the nano service. If a service instance requires the new changes to be applied, you must re-deploy it before it is deleted.

When updating nano services, you also need to be aware that any old callbacks, post actions and any other models that the service depends on, need to be available in the new nano service package until all service instances created before the update have either been updated (through a re-deploy) or fully deleted. Therefore, you must take great care with any updates to a service if there are still zombies left in the system.

Adding new components to the behavior tree will create the new components during the next re-deploy (synthetization) and execute the states in the new components as is normally done.

When removing components from the behavior tree, the components that are removed are set to backtracking and are backtracked fully before they are removed from the plan.

When you remove a component, do so carefully so that any callbacks, post actions or any other model data that the component depends on are not removed until all instances of the old component are removed.

If the identity for a component type is removed, then NSO removes the component from the database when upgrading the package. If this happens, the component is not backtracked and the reverse diffsets are not applied.

Replacing components in the behavior tree is the same as having unrelated components that are deleted and added in the same update. The deleted components are backtracked as far as possible, and then the added components are created and their states executed in order.

In some cases, this is not the desired behaviour when replacing a

component. For example, if you only want to rename a component,

backtracking and then adding the component again might make

NSO push unnecessary changes to the network or run delete

callbacks and post actions that should not be run. To remedy

this, you might add the ncs:deprecates-component

statements to the new component, detailing which components it

replaces. NSO then skips the backtracking of the old

component and just applies all reverse diffsets of the deprecated

component. In the same re-deploy, it then executes the new

component as usual. Therefore, if the new component produces the same

configuration as the old component, nothing is pushed to the network.

If any of the deprecated components are backtracking, the backtracking will be handled before the component is removed. When there are multiple components that are deprecated in the same update, the components will not be removed, as detailed above, until all of them are done backtracking (if any one of them are backtracking).

When adding or removing states in a component, the component is backtracked before a new component with the new states is added and executed. If the updated component produces the same configuration as the old one (and no preconditions halt the execution), this should lead to no configuration being pushed to the network. So, if changes to the states are done, you need to take care when writing the preconditions and post actions for a component if no new changes should be pushed to the network.

Any changes to the already present states that are kept in the updated component will not have their configuration updated until the new component is created, which happens after the old one has been fully backtracked.

For a component where only the configuration for one or more states have changed, the synthetization process will update the component with the new configuration and make sure that any new callbacks or similar are called during future execution of the component.

The text in this section sums up as well as adds additional detail on the way nano services operate, which you will hopefully find beneficial during implementation.

To reiterate, the purpose of a nano service is to break down an

RFM service into its isolated steps. It extends the normal

ncs:servicepoint YANG mechanism and requires the following:

-

A YANG definition of the service input parameters, with a service point name and the additional nano-plan-data grouping.

-

A YANG definition of the plan component types and their states in a plan outline.

-

A YANG definition of a behavior tree for the service. The behavior tree defines how and when to instantiate components in the plan.

-

Code or templates for individual state transfers in the plan.

When a nano service is committed, the system evaluates its behavior tree. The result of this evaluation is a set of components that form the current plan for the service. This set of components is compared with the previous plan (before the commit). If there are new components, they are processed one by one.

For each component in the plan, it is executed state by state in

the defined order. Before entering a new state, the create

pre-condition for the state is evaluated if it

exists. If a create pre-condition exists and if it is not

satisfied, the system stops progressing this component and

jumps to the next one. A kicker is then defined for

the pre-condition that was not satisfied. Later, when this kicker

triggers and the pre-condition is satisfied, it performs a

reactive-re-deploy and the kicker is removed.

This kicker mechanism becomes a self-sustained RFM loop.

If a state's pre-conditions are met, the callback function or template associated with the state is invoked, if it exists. If the callback is successful, the state is marked as reached, and the next state is executed.

A component, that is no longer present but was in the previous plan, goes into back-tracking mode, during which the goal is to remove all reached states and eventually remove the component from the plan. Removing state data changes is performed in a strict reverse order, beginning with the last reached state and taking into account a delete pre-condition if defined.

A nano service is expected to have a component. All components are

expected to have ncs:init as its first state and

ncs:ready as its last state.

A component type can have any number of specific states in between

ncs:init and ncs:ready.

Back-tracking is completely automatic and occurs in the following scenarios:

- State pre-condition not satisfied

-

A reached state's pre-condition is no longer satisfied, and there are subsequent states that are reached and contain reverse diff-sets.

- Plan component is removed

-

When a plan component is removed and has reached states that contain reverse diff-sets.

- Service is deleted

-

When a service is deleted, NSO will set all plan components to back-tracking mode before deleting the service.

For each RFM loop, NSO traverses each component and state in order. For each non-satisfied create pre-condition, a kicker is started that monitors and triggers when the pre-condition becomes satisfied.

|

While traversing the states, a create pre-condition that was

previously satisfied may become un-satisfied. If there are

subsequent reached states that contain reverse diff-sets,

then the component must be set to back-tracking mode. The

back-tracking mode has as its goal to revert all changes up

to the state which originally failed to satisfy its create

pre-condition. While back-tracking, the delete pre-condition

for each state is evaluated, if it exists. If the delete

pre-condition is satisfied, the state's reverse diff-set is

applied, and the next state is considered. If the delete

pre-condition is not satisfied, a kicker is created to

monitor this delete pre-condition. When the kicker triggers,

a reactive-re-deploy is called and the

back-tracking will continue until the goal is reached.

|

When the back-tracking plan component has reached its goal state, the component is set to normal mode again. The state's create pre-condition is evaluated and if it is satisfied the state is entered or otherwise a kicker is created as described above.

|

In some circumstances a complete plan component is removed (for example, if the service input parameters are changed). If this happens, the plan component is checked if it contains reached states that contain reverse diff-sets.

|

If the removed component contains reached states with reverse diff-sets, the deletion of the component is deferred and the component is set to back-tracking mode.

|

In this case, there is no specified goal state for the back-tracking. This means that when all the states have been reverted, the component is automatically deleted.

|

If a service is deleted, all components are set to back-tracking mode. The service becomes a zombie, storing away its plan states so that the service configuration can be removed.

All components of a deleted service are set in backtracking mode.

|

When a component becomes completely back-tracked, it is removed.

|

When all components in the plan are deleted, the service is removed.

|

A nano service behavior tree is a data structure defined for each service type. Without a behavior tree defined for the service point, the nano service cannot execute. It is the behavior tree that defines the currently executing nano-plan with its components.

Note

This is in stark contrast to plan-data used for logging purposes

where the programmer needs to write the plan and its components

in the create() callback.

For nano services, it is not allowed to define the nano plan in

any other way than by a behavior tree.

The purpose of a behavior tree is to have a declarative way to specify how the service's input parameters are mapped to a set of component instances.

A behavior tree is a directed tree in which the nodes are classified as control flow nodes and execution nodes. For each pair of connected nodes, the outgoing node is called parent and the incoming node is called child. A control flow node has zero or one parent and at least one child, and the execution nodes have one parent and no children.

There is exactly one special control flow node called the root, which is the only control flow node without a parent.

This definition implies that all interior nodes are control flow nodes, and all leaves are execution nodes. When creating, modifying, or deleting a nano service, NSO evaluates the behavior tree to render the current nano plan for the service. This process is called synthesizing the plan.

The control flow nodes have a different behavior, but in the end, they all synthesize its children in zero or more instances. When the a control flow node is synthesized, the system executes its rules for synthesizing the node's children. Synthesizing an execution node adds the corresponding plan component instance to the nano service's plan.

All control flow and execution nodes may define pre-conditions, which must be satisfied to synthesize the node. If a pre-condition is not satisfied, a kicker is started to monitor the pre-condition.

All control flow and execution nodes may define an observe monitor which results in a kicker being started for the monitor when the node is synthesized.

If an invocation of an RFM loop (for example, a re-deploy) synthesizes the behavior tree and a pre-condition for a child is no longer satisfied, the sub-tree with its plan-components is removed (that is, the plan-components are set to back-tracking mode).

The following control flow nodes are defined:

- Selector

-

A selector node has a set of children which are synthesized as described above.

- Multiplier

-

A multiplier has a foreach mechanism that produces a list of elements. For each resulting element, the children are synthesized as described above. This can be used, for example, to create several plan-components of the same type.

There is just one type of execution node:

- Create component

-

The create-component execution node creates an instance of the component type that it refers to in the plan.

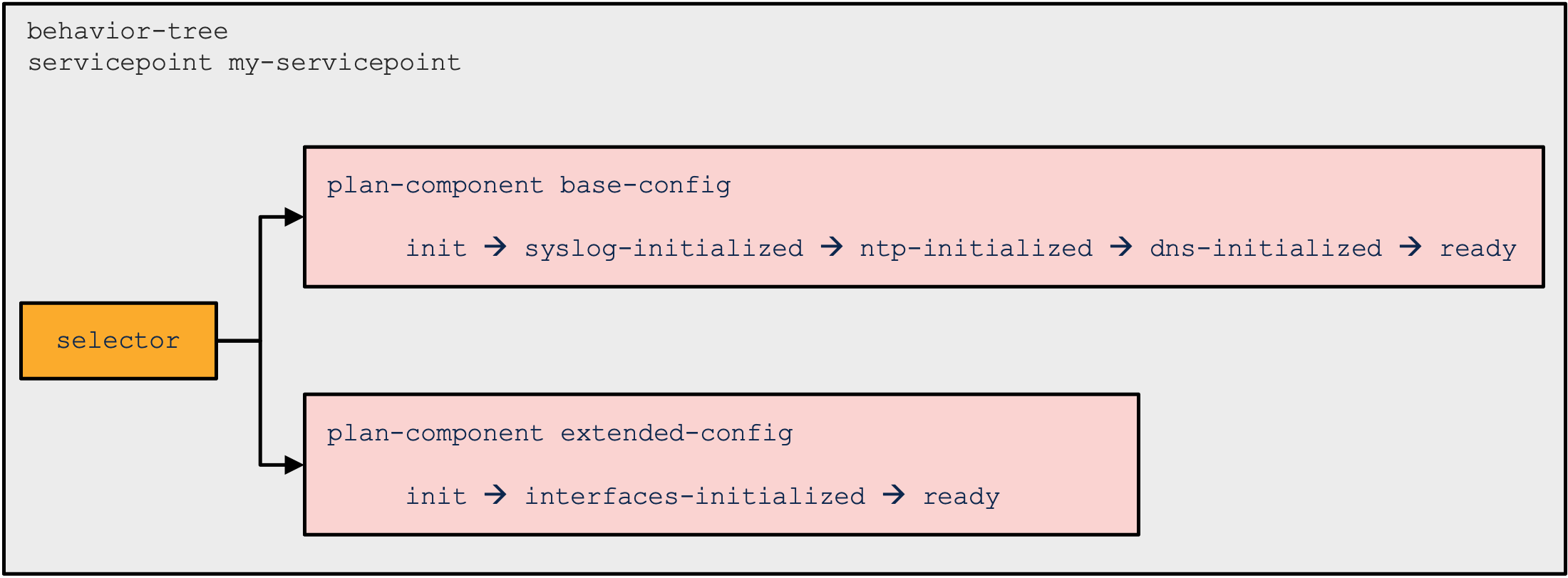

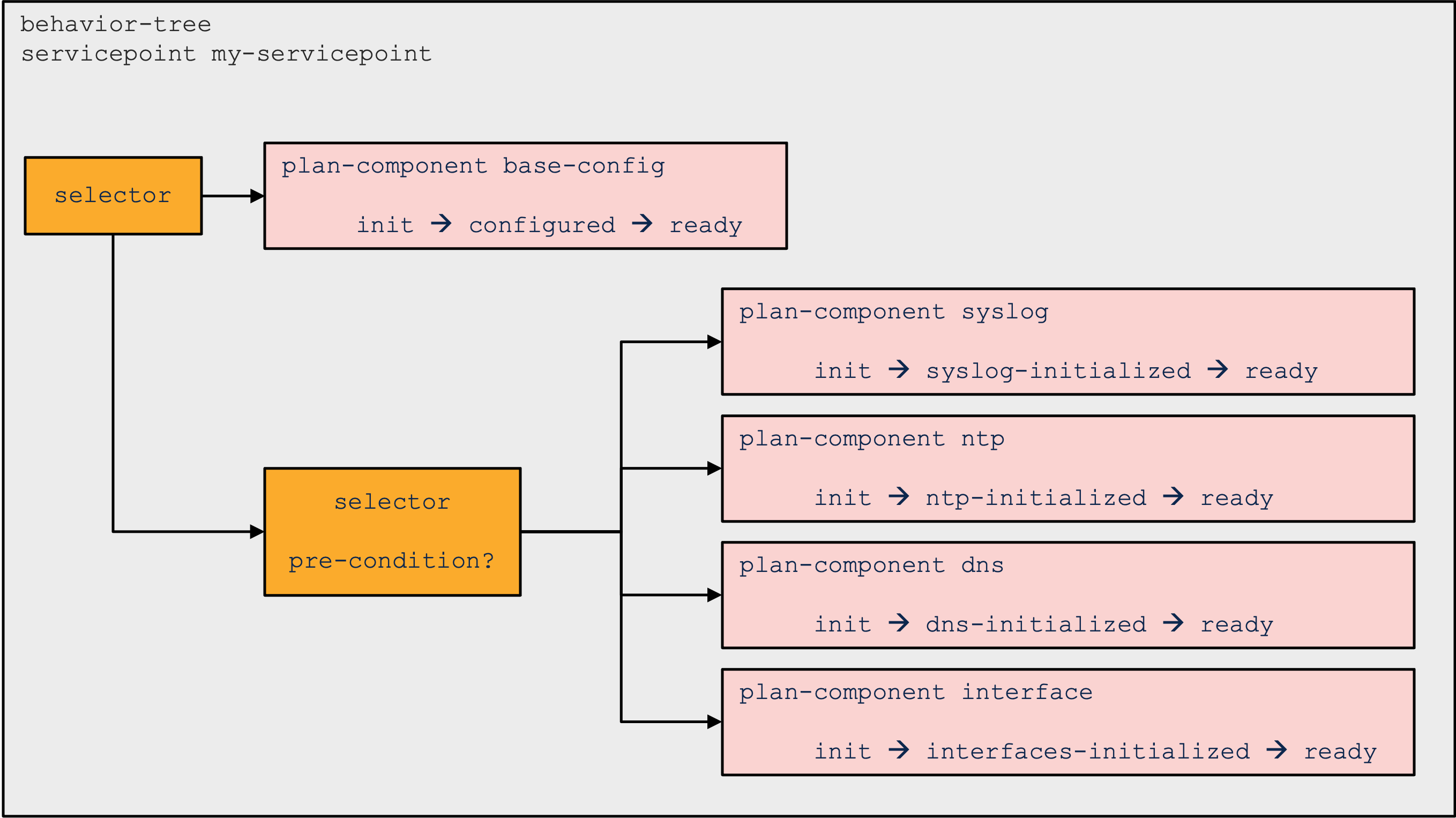

It is recommended to keep the behavior tree as flat as possible. The most trivial case is when the behavior tree creates a static nano-plan, that is, all the plan-components are defined and never removed. The following is an example of such a behavior tree:

|

Having a selector on root implies that all plan-components are created if they don't have any pre-conditions, or for which the pre-conditions are satisfied.

An example of a more elaborated behavior tree is the following:

|

This behavior tree has a selector node as the root. It will always synthesize the "base-config" plan component and then evaluate then pre-condition for the selector child. If that pre-condition is satisfied, it then creates four other plan-components.

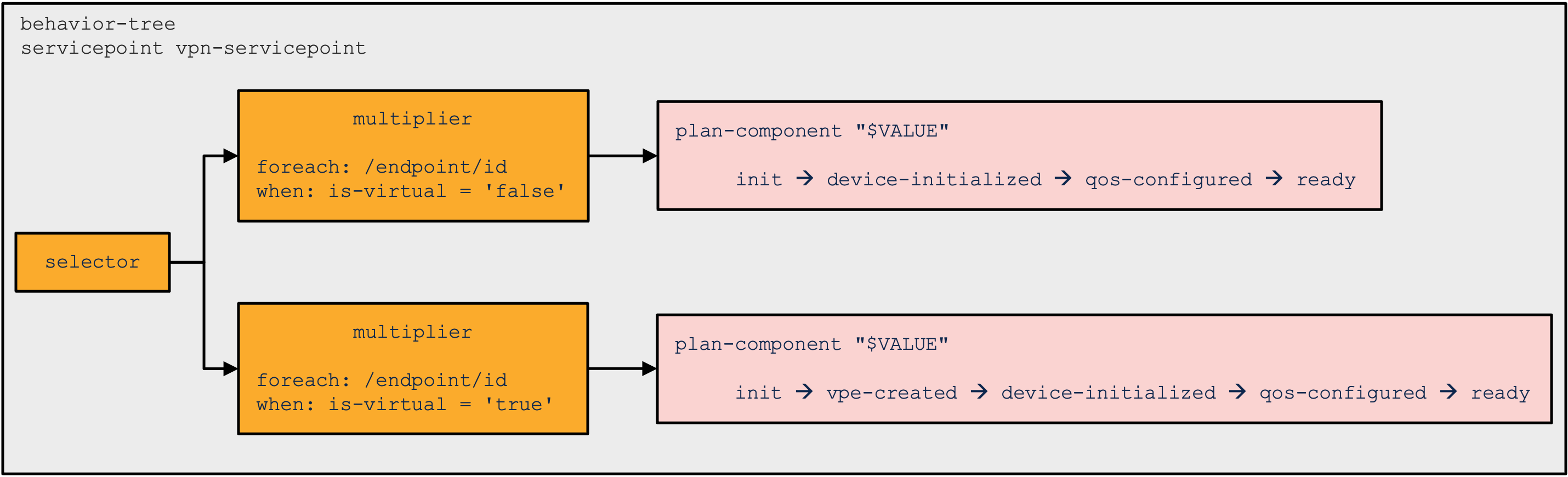

The multiplier control flow node is used when a plan component

of a certain type should be cloned into several copies depending

on some service input parameters. For this reason, the multiplier

node defines a foreach, a when, and a

variable. The foreach is

evaluated and for each node in the nodeset that satisfies the

when, the variable is

evaluated as the outcome. The value is used for parameter

substitution to a unique name for a duplicated plan component.

|

The value is also added to the nano service opaque which enables

the individual state nano service create() callbacks

to retrieve the value.

Variables might also have “when” expressions, which are used to decide if the variable should be added to the list of variables or not.

Pre-conditions are what drives the execution of a nano service. A pre-condition is a prerequisite for a state to be executed or a component to be synthesized. If the pre-condition is not satisfied, it is then turned into a kicker which in turn re-deploys the nano service once the condition is fulfilled.

When working with pre-conditions, you need to be aware that they work a bit differently when used as a kicker to re-deploy the service and when they are used in the execution of the service. When the pre-condition is used in the re-deploy kicker, it then works as explained in the kicker documentation (that is, the trigger expression is evaluated before and after the change-set of the commit when the monitored nodeset is changed). When used during the execution of a nano service, you can only evaluate it on the current state of the database, which means that it only checks that the monitor returns a nodeset of one or more nodes and that trigger expression (if there is one) is fulfilled for any of the nodes in the nodeset.

Support for pre-conditions checking, if a node has been deleted, is

handled a bit differently due to the difference in how the pre-condition

is evaluated. Kickers always trigger for changed nodes (add,

deleted, or modified) and can check that the node was deleted in the

commit that triggered the kicker. While in the nano service evaluation,

you only have the current state of the database and the monitor

expression will not return any nodes for evaluation of the trigger

expression, consequently evaluating the pre-condition to false. To support

deletes in both cases, you can create a pre-condition with a monitor

expression and a child node ncs:trigger-on-delete which

then both create a kicker that checks for deletion of the monitored node

and also does the right thing in the nano service evaluation of the

pre-condition. For example, you could have the following component:

ncs:component "base-config" {

ncs:state "init" {

ncs:delete {

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:monitor "/devices/device[name='test']" {

ncs:trigger-on-delete;

}

}

}

}

ncs:state "ready";

}The component would only trigger the init states delete pre-condition when the device named test is deleted.

It is possible to add multiple monitors to a pre-condition by using

the ncs:all or ncs:any extensions.

Both extensions take one or multiple monitors as argument.

A pre-condition using the ncs:all extension is satisfied

if all monitors given as arguments evaluate to true. A pre-condition

using the ncs:any extension is satisfied if at least

one of the monitors given as argument evaluates to true.

The following component uses the ncs:all and

ncs:any extensions for its self

state's create and delete pre-condition, respectively:

ncs:component "base-config" {

ncs:state "init" {

ncs:create {

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:all {

ncs:monitor $SERVICE/syslog {

ncs:trigger-expr: "current() = true"

}

ncs:monitor $SERVICE/dns {

ncs:trigger-expr: "current() = true"

}

}

}

}

}

ncs:delete {

ncs:pre-condition {

ncs:any {

ncs:monitor $SERVICE/syslog {

ncs:trigger-expr: "current() = false"

}

ncs:monitor $SERVICE/dns {

ncs:trigger-expr: "current() = false"

}

}

}

}

}

}

ncs:state "ready";

}

The service opaque is a name-value list that can optionally be

created/modified in some of the service callbacks, and then

travels the chain of callbacks

(pre-modification, create, post-modification). It is returned by

the callbacks and stored persistently in the service private

data. Hence, the next service invocation has access to the

current opaque and can make subsequent read/write operations to

the same object.

The object is usually called opaque in Java

and proplist in Python callbacks.

The nano services handle the opaque in a similar fashion, where a callback for every state has access to and can modify the opaque. However, the behavior tree can also define variables, which you can use in preconditions or to set component names. These variables are also available in the callbacks, as component properties. The mechanism is similar but separate from the opaque. While the opaque is a single service-instance-wide object set only from the service code, component variables are set in and scoped according to the behavior tree. That is, component properties contain only the behavior tree variables which are in scope when a component is synthesized.

For example, take the following behavior tree snippet:

ncs:selector {

ncs:variable "VAR1" {

ncs:value-expr "'value1'";

}

ncs:create-component "'base-config'" {

ncs:component-type-ref "t:base-config";

}

ncs:selector {

ncs:variable "VAR2" {

ncs:value-expr "'value2'";

}

ncs:create-component "'component1'" {

ncs:component-type-ref "t:my-component";

}

}

}